Should you measure your training load?

Leave a CommentThe benefits and pitfalls of using technology to monitor training.

There are many different ways of measuring the work you do in training.

If you are doing a single discipline sport like swimming or running or cycling then you could use a simple metric such as distance covered.

But using just one ‘easy to measure’ number would then mean that your 10km ‘easy’ run on a Sunday would then look a lot tougher on paper (or screen) than your 6 sets of 60-metre hill sprints at ‘full speed‘ on a Monday even though the purpose of each session is different.

With all the recent developments in training technology, much of which is becoming affordable (just) for the recreational athlete, it is easy to get lost in the Data Smog.

In this blog, I will outline a simple measuring tool that allows you to measure your overall training load across all your sessions. It will then look at how to use that information on a weekly and monthly basis to plan your training and reduce the chances of overtraining or illness.

I include the Case Study of a Modern Pentathlete who has to juggle 5 disciplines and her supplemental training and how this tool helps her.

Why measure training load?

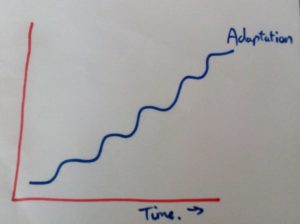

The underlying premise when coaching athletes is to plan and measure progress to achieve a goal. A combination of training and adequate recovery allows the body to adapt and become better at doing what it has been practising (1,2).

Too much work and too little recovery lead to staleness, illness and potentially burnout or injury. Too little work and too much recovery mean your performance either stays the same or regresses.

Measuring the work accurately allows each athlete to gain a better understanding of what works for them as long as performance is measured too. Just measuring work, without any idea of performance has little relevance.

A simple example is trying to lose weight. Usually, more work done equals more calories burnt. But an example of unexpected outcomes that occur when just focussing on work was the well-reported study from the University of Pittsburgh that looked at fitness trackers and weight loss (3).

This well-designed study that monitored 471 subjects over 2 years found that those subjects who used the trackers actually lost less weight compared to those with no trackers. The researchers thought that by providing more data on work done, those subjects would be encouraged to do more. The opposite happened.

This study had far more subjects and was conducted over a far longer time than almost all of the studies looking at athletes and training loads. The key message is that the measuring can be a distraction from the performance (weight loss in this case), which is dependent on many other factors.

What about measuring GPS, Heart Rates, Lactate Thresholds or Power Outputs?

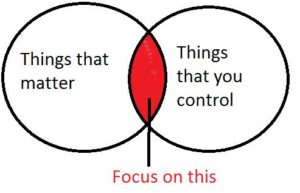

I often see people measuring things that appear to have little relevance to performance. They measure things because they can be measured, rather than thinking “Will this help me go faster?”

No one ever won an Olympic Medal for having the best Heart Rate, Lactate or Power outputs. People win medals by crossing the line first, jumping further, lifting heavier things or throwing things further.

Whilst “marginal gains” has become a popular mantra, this only applies to a very few people. Instead, most gains can be made by focussing on one or two big, important, variables that really impact your performance. Measuring those and then manipulating them so that your body adapts will lead to a performance improvement.

There are more than one or two things that affect your performance, and it is easy to get distracted by measuring minor influences because your friend uses this fancy gizmo.

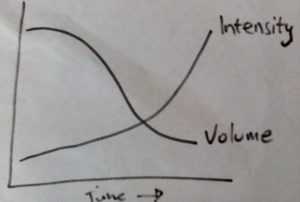

As creatures of habit, many athletes get stuck with a very similar training load each week, or sometimes each day. Having a variety of training, alternating hard and easy days, and adjusting training from week to week are sound training principles that allow sustained progress and adherence.

If an athlete just trains on feel or believes that every session has to be hard, then burnout, staleness and injury can occur. By monitoring training load, the athlete can see if they have been following the plan, or whether they have got stuck in a rut.

Problems with measuring training loads

Before reviewing some training load options, it is important to understand that the body is a complex organism and many factors outside of training will affect how each athlete adapts. These include:

gender, age, training history, illness, stress, diet, sleep, work, travel, climate, hydration and exams.

If we have two athletes with similar performances in a 5km run of 16 minutes, then a similar training programme may have different results due to the above factors. Monitoring training load is very useful but is only part of the process.

There are three main problems with measuring training loads:

- Reliability: Is the measurement accurate at all times and with all users? A set of scales should be easy enough to use by different people from different backgrounds and give accurate results for mass.

Is the same accuracy present when it analyses your body fat percentage? The more complex the measurement, the more room for error. Do pedometers on phones measure distance covered as well as they do steps? (In a sidebar, why measure steps at all?) Be careful about relying on apps.

2. Validity: Is the measurement relevant to your sport?

Is body fat percentage important to you as a cyclist or runner? If so, then those with the lowest body fat percentage would be the fastest. But, is Mo Farah’s bf % low because he trains so much, or can he run fast because he is lean? It is obvious that no runner with 25% bf is going to make an Olympic final, but would 6% vs 7% bf be the deciding factor as both runners are very lean?

A more obvious example would be using a heart rate monitor to measure your gym session. It is irrelevant for what you are trying to achieve unless you are doing a cardiovascular circuit.

3. Transfer: Many of the measurements are modality-specific. Heart Rate is great for endurance work, but this changes according to whether you are running, swimming or cycling. 168bpm means different intensities for all 3 of these activities.

Measuring kilometres covered is highly relevant for cycling, but useless for run speed sessions. 10km would be a tough swim session, but only a warm up for cycling.

Trying to use the same tool to measure different things is common because it is easy. The alternative is often to have different tools for everything, but then you are laden down with data and it all becomes meaningless.

Common Ways to Measure Training Load

Here are some measurement tools with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

To save repetition, remember that these tools are designed to measure a single component of fitness. Adjusting your training to improve these results, rather than what counts in a race: crossing the line first, is the most common error amongst many athletes.

These have some use for the ‘team-skill sports’ but they do not measure the quality of play nor the effectiveness of your play. I.e. you could produce great numbers on the pitch but be as effective as a deckhand on a submarine.

Distance would be an example of this. It is a great tool, but if your training changes so you add more miles to get better scores, but neglect variations of pace, intensity and terrain, you will limit what performance changes you make. This is human nature.

Heart Rate: A very simple method which requires no equipment except a watch. Heart Rate rises with a corresponding increase in effort and work. Therefore, if all else is equal, the workout with the higher heart rate has required more effort and work done (4).

Very useful for comparing like for like workouts over time such as running a fastest mile in 5:30 with a heart rate of 180 beats per minute(bpm). You can then try and match that intensity in sub sets of 800m or 400m. Or try and run the same mile at the end of the training block at the same pace and see if your heart rate is lower or higher, indicating that your heart has got stronger.

“Heart Rate should be an indicator not a dictator.” Bryan Fish.

There are several disadvantages, some of which are due to a misunderstanding of application. Use Heart Rate to help you pace and judge how you feel based on times and distances. The main error is in estimating your maximum heart rate and then planning sessions around percentages of this fictitious maximum.

Instead, use something like running your fastest possible mile to get a closer approximation of what your maximum heart rate is.

Climate, hydration and stress are three of the factors that can influence Heart Rate and therefore it should not be used as the sole indicator (5) of training load.

Distance: A simple and effective measure, made easier with technology. Great for single discipline sports such as running or cycling. Less effective when comparing across disciplines, useless in the weights room (load in kg would work better).

Lactate: Less common now, but very popular twenty years ago when portable lactate testers became accessible and they are still used in swimming. However, there have been many flaws found partly due to outside factors such as carbohydrate ingestion, preceding exercise and muscle damage affecting results (6). Also, the measurement error that arrives from a pinprick of blood outweighs and potential changes in exercise intensity, so you are looking at very flawed data.

GPS: Useful for measuring distance and changes of pace and speed. Very useful to assess and monitor how you change according to terrain and difference portions of the session (7). Do you run even 1km splits or start slower and finish faster? Disadvantages include interpreting this data and using it adjust your subsequent sessions. If you are doing short sprints or change of direction, this data is less accurate (8).

Power Output (Watts): Used extensively by cycling now, but has zero transfer to other sports. Can quantify the work done in each session and is useful in conjunction with distance covered and speed. It allows the cyclist to see if they are adapting to the training.

A simple but effective alternative

A simple measurement tool that I use is the Session Rating of Perceived Exertion (sRPE).

This was first ventured in 1998 by researchers in Milwaukee when trying to quantify training load and identify correlations with overtraining (9).

These researchers faced the same problems already identified about measurement, only some of the tools and technology have changed since. They were trying to identify how much training could be done before an increase in illnesses occurred within athletes.

They found that each athlete had a “training threshold” unique to them and that if they trained above it, illnesses were far more likely to occur. Retrospectively, 84% of illnesses could be explained by a preceding spike in Training Load (TL) above the individual threshold.

Subsequent research has refined the detail of the sRPE.

Her is a quick look at 3 of the variables that were collected from their research and that I have used (the 4th Training Strain I have yet to find useful, but it may be for others).

1.Training Load (TL) = sRPE x duration (mins) of the session. Measured by individual sessions and a daily/ weekly total.

2. Standard Deviation (SD) = how much difference there is between the sessions compared to the average session.

3. Training Monotony (TM)= Average daily training load/ SD

Training Load uses a modified scale of Borg’s Rating of Perceived Exertion as the basis of sRPE (10, Table1). Athletes can gauge quite well how hard their session was with only a small amount of practice; it is best done 30 minutes after a session has finished, to allow a more reflective and accurate approach to be taken.

This needs to be measured after every training session and recorded. A daily and weekly total then needs to be calculated.

Table 1 Modified Borg scale of Session RPE

| Session RPE scale | |

| 0 | Rest |

| 1 | Really Easy |

| 2 | Easy |

| 3 | Moderate |

| 4 | Sort of Hard |

| 5 | Hard |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Really hard |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Really, really hard |

| 10 | Just like my hardest race |

Standard Deviation is a statistical tool that is necessary to allow us to calculate the Training Monotony. I was a bit concerned about the Maths at the start, but setting it up on the spreadsheet was easy enough using the inbuilt formulae. Standard Deviation was the only part that needed refreshing in my memory, having last used it 30 years ago.

Training Monotony is a very important number that shows how much or how little variation occurs within the training. The dangers of monotonous training were first found in racehorses but have since been found in endurance athletes too (11-13). There is a psychological component to Overtraining and doing the same type of training too often with little variation appears to be a big factor.

The TM figure should be as close to 1.0 as possible. This shows that you have lots of variation between your days. On paper, you may plan a variety of sessions, but each day and potentially each week could end up being very similar in Training Load and therefore you have Training Monotony.

The advantage of sRPE is that you can compare effort across different types of sessions: running, swimming, weight training and cycling. This allows an overall look at the total work done in a week, rather than adding up different forms of data from individual sessions and trying to make sense of it all. This is especially useful in multi-discipline athletes as you will see in the case study.

Case study

A 23-year-old Modern Pentathlete who has recently started full-time work.

Previously she was able to rest in between sessions and manage her week around training. Now she has to train before and after work and at weekends. Concerned with how this may add to the overall load, we decided to try using sRPE to monitor load and variety.

Here are her results from two consecutive weeks of training, and comments about how we have adapted as a result.

Week 1

| Day | Session | Duration | SRPE | Session TL | Daily TL |

| Monday 5th | swimming | 50 | 4 | 200 | 470 |

| weights | 40 | 6 | 240 | ||

| shooting | 15 | 2 | 30 | ||

| Tuesday 6th | swimming | 45 | 5 | 225 | 395 |

| running | 35 | 4 | 140 | ||

| shooting | 15 | 2 | 30 | ||

| Wednesday 7th | swimming | 45 | 4 | 180 | 390 |

| weights | 60 | 3 | 180 | ||

| shooting | 15 | 2 | 30 | ||

| Thursday | swimming | 60 | 7 | 420 | 620 |

| running | 40 | 4 | 160 | ||

| shooting | 20 | 2 | 40 | ||

| Friday | swimming | 35 | 5 | 175 | 355 |

| riding | 60 | 3 | 180 | ||

| Saturday | running | 45 | 4 | 180 | 180 |

| Sunday (rest day) | riding | 90 | 3 | 270 | 270 |

| Summary | Total TL | 2060 | |||

| Average Daily TL | 294.29 | ||||

| SD Daily TL | 140.65 | ||||

| Training Monotony | 2.09 |

Week 2

| Day | Session | Duration | SRPE | Session TL | Daily TL |

| Monday | running | 40 | 6 | 240 | 620 |

| weights | 50 | 7 | 350 | ||

| shooting | 15 | 2 | 30 | ||

| Tuesday | swimming | 50 | 7 | 350 | 605 |

| shooting | 15 | 2 | 30 | ||

| running intervals | 45 | 5 | 225 | ||

| Wednesday | swimming | 50 | 9 | 450 | 730 |

| weight lifting | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||

| Speed drills | 20 | 4 | 80 | ||

| Thursday | running | 40 | 6 | 240 | 490 |

| riding | 50 | 5 | 250 | ||

| Friday | running | 40 | 4 | 160 | 180 |

| shooting | 10 | 2 | 20 | ||

| Saturday | swimming | 60 | 3 | 180 | 660 |

| fencing (competition) | 120 | 4 | 480 | ||

| Sunday | 0 | 200 | |||

| riding | 50 | 4 | 200 | ||

| Summary | Total TL | 2995 | |||

| Average Daily TL | 427.86 | ||||

| SD Daily TL | 222.26 | ||||

| Training Monotony | 1.93 |

The main difference between Week 1 and Week 2 was the fencing competition on the 2nd Saturday which she won. The idea was to use this as a “tough” training environment, but in the end she won comfortably.

Other differences can occur with seemingly small changes. For example, by adding 10 extra minutes to her Monday weights, with a small increase in intensity, the actual training load increased by 46%!

| Week 1 Monday weights | 40 | 6 | 240 |

| Week 2 Monday weights | 50 | 7 | 350 |

A similar thing happened on the following morning’s swim session, resulting in an increase of 55%!

| Week 1 Tuesday | swimming | 45 | 5 | 225 |

| Week 2 Tuesday | swimming | 50 | 7 | 350 |

What should happen is that looking at these two increases, a corresponding decrease should take place on the Wednesday. Instead, she carried on as normal and actually increased the workload due to a tough swimming session, going from TL 390 to TL 730 a whopping 87% increase.

But, going into the competition she did reduce training somewhat over the Thursday and Friday in week 2 compared to week 1 and got the desired result.

The training monotony is too high for both weeks (1.93 and 2.09); we need to move this closer to 1.0. There is only one really hard day with TL over 700, but several in the 600s, none in the zeros, 100s or 500s.

The “rest day” of riding in week 1 was not resting enough with TL 270 due to the amount of time spent on the horse. We shall look closely at how to add more variety, and I will reinforce the need to “rest” and that easy means easy.

There are three key points for readers to note from this case study:

1. Small individual changes can make a big difference in total over the week.

2. The results must be recorded immediately and looked at; so that changes can be made to the following day’s training.

3. Training Monotony creeps up on you if you are not careful. Whilst individual sessions are different, the TL needs to differ day-to-day too.

Summary

Technology is developing rapidly and so is its availability to recreational athletes. It is easy to get caught up in measuring things without understanding if and how they affect your overall goal. Using sRPE may be a simple tool that allows you to get an overall picture and ensure that you have plenty of variety in your training.

This should be used to compare results on an individual basis, rather than using it to compare athletes. There is no “one size fits all” training plan. Athletes respond differently and so the loads will differ for optimal training.

Alternating easier and harder days is a fundamental training principle, with hard being hard and easy being easy. This will allow you to train effectively over longer periods of time which then leads to better results.

Further Reading:

References

1. Sports Med 39 p779–795 (2009)

2. Sports Med Phys Fitness 49 p333–345 (2009)

3. JAMA 316(11) p1161-1171 (2016).

4. J Sports Sci 16 p53–57 (1998).

5. J Sports Sci 16 p85–90 (1998).

6. S. J Sports Med 16 p3–7 (2004).

7. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 40 p124–132 (2008).

8. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 5 p406-411(2010).

9. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30(7) p1164-1168 (1998).

10. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 65 p679-685 (1987).

11. Appl. Physiol.7 (6) p1908-1913 (1994).

12. JSCR 15(1) p109–115 (2001).

13. S. J Sports Med. 18 p14–17 (2006).

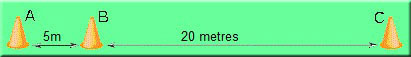

The Yo-Yo may have been around for nearly 1000 years, but today a new form of Yo-Yo is a regular fixture in Sport’s coaches’ fitness testing toolbox.

The Yo-Yo may have been around for nearly 1000 years, but today a new form of Yo-Yo is a regular fixture in Sport’s coaches’ fitness testing toolbox.

We have a high tech facility with 2 skiing treadmills and the ability to provide athletes oxygen supplementation to simulate a variety of altitudes. We do all max VO2 tests at sea level conditions. We test our athletes rollerskiing for specificity.

We have a high tech facility with 2 skiing treadmills and the ability to provide athletes oxygen supplementation to simulate a variety of altitudes. We do all max VO2 tests at sea level conditions. We test our athletes rollerskiing for specificity. We have tests that compliment and verify one another. For example, we have VO2, hemoglobin mass and blood testing. A low VO2 might be due to low ferretin.

We have tests that compliment and verify one another. For example, we have VO2, hemoglobin mass and blood testing. A low VO2 might be due to low ferretin.