Why most hamstring exercises don’t work for running.

11 CommentsThe Great Hamstring Saver?

A recent article in the New York Times hailed the Nordic Hamstring Exercise as the saviour of all athletes involved in explosive sports. Citing several published papers, the NYT suggests that this single exercise could put an end to the dreaded hamstring injuries.

We take a more in depth look at the implications of the Nordic Hamstring Exercise relating to both injury reduction, and performance.

Prevalence of hamstring injuries

Hamstring injuries are common in sports characterized by maximal sprinting, kicking and sudden accelerations. Studies have shown that hamstring strains account for about 29% of injuries among sprinters, 16–23% of injuries in Australian Rules football and 12– 16% of all injuries in soccer.1

The recent Rugby Football Union (RFU) Injury Audit showed that 92% of all hamstring injuries were running related, and were the most common training injury.

Not only are they very common, hamstring injuries can also cause significant time loss from competition and training. A rate of 5 to 6 hamstring strains per club per season has been observed in English and Australian professional soccer, resulting in an average of 15 to 21 matches missed per club per season.3

With this in mind, training methods to reduce hamstring injuries should be at the forefront of preparation for athletes of these sports.

What causes hamstrings injuries?

In order to be able to reduce the likelihood of injuries, it is first necessary to identify and understand the factors that contribute to hamstring injuries.

“ EMG analyses during sprinting have shown that muscle activity is highest during the late swing phase, when the hamstring muscles work eccentrically to decelerate the forward movement of the leg”. 1

It has been reported that most hamstring strains occur during maximal sprinting, as this is when the forward movement of the leg is at its fastest. The eccentric overload could put strain on the hamstring muscle and lead to injury. This overload is likely to be exacerbated by inadequate muscle strength.

It has also been suggested that hamstrings are susceptible to injury during the rapid change from their eccentric to concentric action, at the start of the downward swing of the leg. At a high intensity, the force exerted whilst changing the direction of the leg may exceed the limits tolerated by the muscle. This suggests that strength imbalance is also a factor in hamstring injuries.3

Among 64 track and field athletes, 24.2% had suffered from hamstring strains in a two year period following assessment of hip and knee flexion and extension. When these subjects were divided into injured and uninjured groups and compared using the various strength measures, the injured group had greater bilateral imbalance e.g. relatively weak hamstrings compared to quadriceps on either side.6

A literature review during the same study also reported how contralateral (side-to-side) strength imbalances could pose a similar risk for injury. A trend for higher injury rates was found in female collegiate athletes who had strength imbalances of 15% or more on either side of the body. (Ebook on strength for females here)

Strength imbalance of the hamstring muscles compared to quadriceps and contralateral imbalances are both major causes of strains.

Whilst strength is one aspect, timing of contractions could be more important. If the hamstrings are working too late in the running pattern, they will be ineffective in slowing the leg down and may therefore get injured.

Is the Nordic Hamstring the cure?

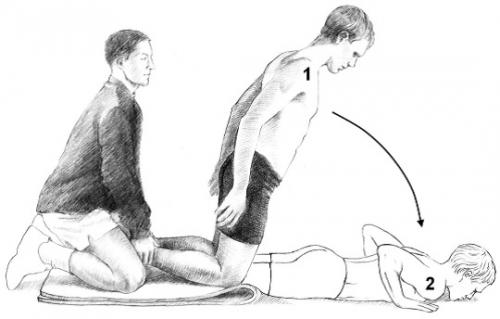

Figure 1.0 The Nordic Hamstring (NH) exercise. The subject attempts to resist a forward-falling motion using his hamstrings to maximize loading in the eccentric phase. The subject should aim to brake the forward fall for as long as possible using their hamstrings.

A program based around the NH exercise (sets of 12, 10 and 8 repetitions) has been shown to increase eccentric hamstring strength in soccer players when performed 3 times a week over a 10 week period.6 Eliminating strength imbalances in athletes with bilateral hamstring asymmetries has been shown to reduce frequency of injury. 4

However, the NH exercise only impacts on eccentric strength of the hamstring during knee extension. (Most studies also test hamstring strength performing knee flexion/extension, using a dynamometer in a seated position).

However, the concept of “eccentric- concentric” action is an oversimplistic view. The hamstrings actually act isometrically at top end sprinting, with the elastic properties of the tendons being used to transfer energy.

When running, the knee angle does not change dramatically, meaning the length of the hamstring muscle stays relatively fixed. Instead, the biarticular hamstrings (particularly the tendons) work eccentrically to decelerate the leg during the forward swing. Therefore NH does not replicate the actions of the hamstring muscle during running.

“Functional training of the hamstrings should therefore not be done through eccentric training, but in an elastic-isometric way, reflecting hamstring functioning during sprinting.”

So does NH prevent hamstring injuries?

In One study, Soccer Players performed a conditioning program for 9 months, after which, the individuals with a previous imbalance had reduced frequency of injury, similar to individuals with no initial imbalance. 4 Furthermore, the players with untreated strength imbalances were found to be 4 to 5 times more likely to sustain a hamstring injury when compared with the normal group.

Despite the apparent success of the above study, the details of the conditioning program undertaken were not given. This could mean that a number of possible exercises, or combinations of exercises were used, making conclusions about the NH impossible.

Further studies however have described how a conditioning programme of NH is effective in reducing prevalence of both new and recurring hamstring injuries. 1, 2, 8, 9

The results of these studies are positive for athletes and coaches involved in sports involving maximal sprinting as the use of the NH could potentially be effective in reducing injuries.

So is the Nordic Hamstring all that?

Despite the positive findings of these studies, there are limitations with this research that should be considered.

- Lack of randomised trials within some studies

- Inconsistencies with frequency of injury monitoring (In one study 1, control group were monitored daily, whereas intervention group only monitored at matches, making it possible that injuries could go unrecorded)

- Inconsistencies with thoroughness of injury measurement (some groups used MRI and ultrasound to detect/confirm injuries, others only used judgment of physical therapist.)

- Possible confirmation bias (therapists expecting less injuries in intervention groups or vice versa could potentially downplay severity of injuries, skewing results)

- No studies compare other possible eccentric exercises, so could be a case of “better than nothing”.

One important note of these studies 1,2 is the timing of the interventions. In Both cases, NH was used as part of a pre-season strengthening intervention, meaning an absence of high intensity and volume of matches. Many experienced coaches such as Vern Gambetta have reported an increase in hamstring injuries when the volume of hamstring loading is high, caused by excessive fatigue. Although the participants in the studies may have continued the NH during the season 1, it was only once a week, allowing the hamstrings time to recover.

One major downfall of the NH is that the hip remains in a fixed position while the hamstrings contract. By working with the hip in a fixed position, the exercises fail to replicate the movement patterns that occur during running. The Hamstrings are biarticular, passing over both the hip and knee joints, and during running they play an active role in hip extension as well as knee flexion.

“Therefore the effects of the Nordic hamstring exercise on running performance can be questioned, despite the possible effects on injury prevention.” 10

What should I do to protect my hamstrings from injury?

Strength training is mode specific meaning that the body will adapt to the specific stimulus placed upon it.

Strength training is mode specific meaning that the body will adapt to the specific stimulus placed upon it.

It could therefore be suggested that to strengthen the hamstrings effectively to reduce injury and also maximise sprinting ability, exercises should be eccentric in nature but also replicate the movement patterns of running.1, 5

(The Run Faster ebook combines specific resistance training exercises and run drills that follow this protocol. It has proven very effective).

Exercises such as Good Mornings/Stiff Leg Deadlifts strengthen the hamstrings eccentrically whilst involving flexion of the hips and would therefore more closely match the specific physiological demands of running than the NH.

Concentric style hamstring exercises such as machine curls are another common method of conditioning.1 However, concentric exercise tends to reduce sarcomere numbers in muscle fibres and consequently results in muscle operating optimally at shorter lengths.3

This training effect raises the susceptibility of the muscle to damage from eccentric exercise. It should therefore be recommended that concentric style conditioning exercises for the hamstrings should be avoided in sports characterised by maximal sprinting efforts.

Other Measures to prevent injury

There are also measures which athletes can take during competition to reduce the chances of hamstring injuries. Hamstring strength has been found to deteriorate throughout the duration of a soccer game, and this fatiguing effect was consistent with a higher injury risk during sprinting movements. 5

Interestingly it was also found that the halftime interval produced a negative influence on eccentric hamstring strength. After remaining seated, strength was lower after half time than at the end of the first half.

This suggests that performing a ‘re-warm up’ after half time may be beneficial, especially with the high injury rates found in the early stages of the second half.

Take Home Message

The high prevalence of hamstring injuries in sports involving maximal sprinting and acceleration shows the importance of an effective conditioning programme for the hamstrings.

Experience of many practitioners suggests that too much eccentric loading before maximal intensity sprinting can lead to injury. Therefore high volume/intensity strength work should be completed outside of competition, with more low volume specific work being done in season.

This includes using:

All found in our Run Faster ebook .

Or look out for our speed training workshops.

Matt Durber

References

1) Arnason, A., Andersen, T.E., Holme, I., Engebretsen, L. & Bahr, R. (2008) Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 18 (1), 40-48.

2) Askling, C., Karlsson, J. & Thorstensson, A. (2003) Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 13, 244-250.

3) Brocket, C.L., Morgan, D.L. & Proske, U. (2004) Predicting hamstring strain injury in elite athletes Medicine and Science in Sports Exercise, 36 (3), 379–387.

4) Croisier, J.L., Ganteaume, S., Binet, J., Genty, M. & Ferret, J.M (2008) Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: A prospective study American Journal of Sports Medicine, 36, 1469-1475.

5) Greig, M. & Siegler, J.C. (2009) Soccer-specific fatigue and eccentric hamstrings muscle strength Journal of Athletic Training, 44 (2), 180-184.

6) Mjolsnes, R., Arnason, A., Osthagen, T., Raastad, T., & Bahr, R. (2004) A 10-week randomized trial comparing eccentric vs. concentric hamstring strength training in well-trained soccer players Scandanavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 14, 311-317.

7) Newton, R.U., Gerber, A., Nimphius, S., Shim, J.K., Doan, B.K., Robertson, M., Pearson, D.R., Craig, B.W., Hakkinen, J. & Kraemer, W.J. (2006) Determination of functional strength imbalance of the lower extremities Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(4), 971–977.

8) Petersen, J., Thorborg, K., Nielsen, M.B., Budtz-Jorgensen, E. & Holmich, P. (2011) Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in men’s soccer: a cluster-randomized contolled trial American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39 (11), 2296-2304.

9) Schache, A. (2012) Eccentric hamstring muscle training can prevent hamstring injuries in soccer players Journal of Physiotherapy, 58 (1), 58.

10) Van Hooren B., Bosch F. (2016). Influence of Muscle Slack on High-Intensity Sport Performance: A Review. Strength and Conditioning Journal 38 (5) p75-87.

It is recommended that the more difficult tasks are perfected on a stable surface before progressing to a rebounder or unstable surface.

It is recommended that the more difficult tasks are perfected on a stable surface before progressing to a rebounder or unstable surface.

I went to netball training last night with the Tiverton Terriers. It was a cold, damp evening with areas of surface water on the court. It was the first session of the year, all of us de-conditioned from the Christmas break but pleased to be back to enjoy the game and catch up with friends.

I went to netball training last night with the Tiverton Terriers. It was a cold, damp evening with areas of surface water on the court. It was the first session of the year, all of us de-conditioned from the Christmas break but pleased to be back to enjoy the game and catch up with friends.