Steve Magness on the Volume Trap

“How many miles should I run”?

Is the question that endurance coach Steve Magness gets asked the most when presenting at workshops. His seminar at this year’s GAIN covered volume and other training parameters which apply to many different sports.

“There is no difference between 99 miles and 100 miles, but people want to get to triple digits” (and therefore earn the right to wear the hair shirt and flail themselves). The same applies to team sports with soccer players trying to run 11km in one session because someone told them that’s what they do in a match.

Steve gave two main reasons for this behaviour:

- It’s human nature to be obsessed with volume. It’s the simplest thing we can measure, so let’s measure it. (If people see me out for a run, the first thing they always ask is “How far did you go?” never “How fast did you run?”).

- We have a deep NEED for classification. It’s the downside to “what gets measured gets managed”. When we are categorised and accept a label we can then defend our label. “I’m a low mileage/ high intensity coach” etc.

Training load calculation

Training load is a commonly used form of measurement.

Training load = training volume x intensity But this is too simplistic. What type of load is it?

- Metabolic

- Biomechanical

- Neural

- Psychological

How about when the load is applied?

- Intensity

- Density

- Frequency

- Rest Periods

How does this relate to daily and weekly sessions?

- Front Loaded

- Back Loaded

How can one number express all this accurately or in a meaningful fashion?

Weekly Training Load

Steve broke down the weekly training load of one of his runners.

- 90 miles per week

- 10.5 hours of training (I made the point that this is for good runners; recreational runners who tried to copy the miles would actually be on their feet for a lot longer).

- 76550 calories burned

- 25,920ml of Oxygen consumed.

Volume has become a marker for “load” and has become a surrogate for physical stress. It is assumed the training “stimulus” leads to a kind of adaptation.

Instead we should look at how much we NEED to do to get the positive adaptation. For example in the weekly schedule above the loading on the achilles tendon may be the weakest link and therefore limit what another athlete can do.

Common assumptions

Steve gave us 3 common assumptions that may be less than certain in reality.

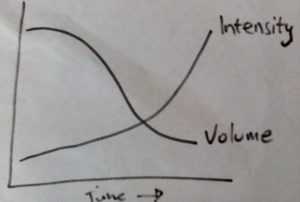

Assumption 1: Volume and Intensity training interact in a simplistic fashion.

Instead there is a constant interplay that changes within each session, each week and over the longer course of a year.

Assumption 2: Volume = ONLY way of getting aerobic adaptation.

This is simply incorrect there are many other ways of stimulating the aerobic system.

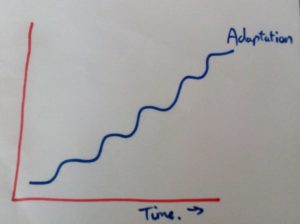

Assumption 3: Adaptation looks like this

Instead, variability is the name of the game. There is a 10% rule of thumb for volume increases, but Steve gave examples from his younger self where increases were much more than this and he could adapt.

The amount of training depends on:

- The athlete perception of normal (a 120 mile a week runner given 90 miles would consider this light, a 50 mile a week runner may well panic!)

- Physiological adaptations.

- Tendon and muscle rate of adaptation: different from each other and also between athletes.

- Bone Turnover (diet surely has an impact on this too?)

Steve’s Old Man Strength

Steve then gave us examples of how he could train with his athletes using his “Old man strength” (Steve is only 32 and a middle distance runner, I really need to pull him aside next time I see him!)

He can do the sessions thanks to an accumulated, consistent training load over time. Younger athletes can indeed increase their volume with age, after that they can reduce it and preserve it by working on specific volumes.

Steve talked about the psychology of volume which I have found to be true depending on the athlete. Sometimes you have to adapt the programme to what the athlete feels they “need” or at least swing the pendulum in that direction.

He then asked us to “flip the switch” and that it’s not about

Volume to get adaptation

It’s thinking about

Adaptation and then how much volume is needed?

“Volume is not a master control switch”

Alternative ways of developing aerobic system to volume

Steve then gave some examples and case studies of how the aerobic system can be developed in middle distance runners without just adding more weekly mileage.

Recreational runners please take note: you do not have the time to do the mileage if you are running slower than 5-6 minute miles. If you try and copy the mileage plans of faster runners you will be spending a lot more time training than they do!

Some session examples include:

- Pre fatigue: do a shorter “long run” the day after an intense workout.

- Doubles: do 2 shorter runs in a day, helps with lifestyle too.

- Strength session followed by endurance work. You are forced to train in this fatigued state.

- Ending the session or cool downs with “stuff”. For example an 800m “cruise” to work at the high end of aerobic system and get used to preserving strength at the end of a race.

Steve then gave some examples of sessions which he has done with his athletes including the sets/ reps and different ideas. All of these worked with his athletes and in their context.

(I often see endurance coaches trotting out a session like “Oregon circuits” or such like and inflicting it upon their athletes year after year without understanding why. So I won’t post the details here to avoid feeding the monster, but I will use some of the ideas with Excelsior ADC athletes).

Measuring for measuring sake

Steve finished his seminar with some questions about measuring sessions and how these questions can then shape what we do as coaches.

If athletes are constantly looking at technology, how can they “feel” what they are doing? (Luke destroyed the Death Star by using the Force remember, not by looking at his Garmin).

This is even assuming you are measuring the right thing. I have written elsewhere about the addiction to measuring technology and how that can then alter the design of sessions. The tail wags the dog. Bryan Fisher summed it up a few years ago at GAIN

“Heart rate should be an indicator not a dictator”.

Ask yourself these questions when developing a middle distance running plan (or any other plan for that matter) for an athlete:

- In what direction are we trying to adapt?

- Where have they been in the past?

- Are they still adapting?

- What is their injury history and adaptability?

- What is the risk: benefit ratio of your programme will it cause adaptation or maladaptation/ injury?

- Are we measuring the right thing?

- Is that measurement what you think it is?

Is the answer to any of these questions “You should run X miles per week” ?

The answer isn’t to be anti-volume or pro-volume, it is to sit down and think about the athlete in front of you and work out what is right for them. How many coaches take the time to do that?

Summary

I have known Steve for 5 years now and used many of his principles with our athletes. Until I met him, much of the endurance coaching I had seen or read was very patchy and full of mystical secrets or folklore.

Much like when I first saw Frans Bosch present on sprinting in 2009, I had an “Aha” moment and thought this makes sense (although Frans didn’t make any sense the first 3 times I saw him, but I could see it worked). Steve is very good at expressing complex ideas simply.