Posts Tagged ‘overtraining’

Periodization: beginners guide

What is Periodisation?

Most people start off with Tudor Bompa’s Periodization or, in this country, Frank Dick’s sports training principles when learning about periodisation. They cover the basis premise about modulating volume and intensity over a period of time to allow overload and adaptation to take place.

Read MoreTraining Design Do’s and Don’ts: Gary Winckler

Train to the athlete’s strengths

Gary Winckler has 38 years of coaching experience behind him. He has taken track athletes to every Olympic Games since the 1984 Olympics.

(Pictured to my right, with P.E. specialist Greg Thompson)

More impressively, each of those athletes has had a Personal Best or Season Best at the Games.

He knows how to prepare for the big event.

Read MoreMonitoring Overtraining: The 4 Hs

“You’ve Got To Be In Top Physical Condition. Fatigue Makes Cowards Of Us All.

Vince Lombardi.

Vince Lombardi.

But, in order to get in top physical condition, athletes risk doing too much, resting too little and can get fatigued.

Read MoreIs my child overtraining?

Exam season is upon us, and they may have pushed your teenager to breaking point

Overtraining is common in young athletes due to the high demand put on them by schools and sports teams.

Overtraining is common in young athletes due to the high demand put on them by schools and sports teams.

Schools will get talented young athletes to compete in as many sports as possible and these same athletes will also train outside of school for a team they play for in one or more sports.

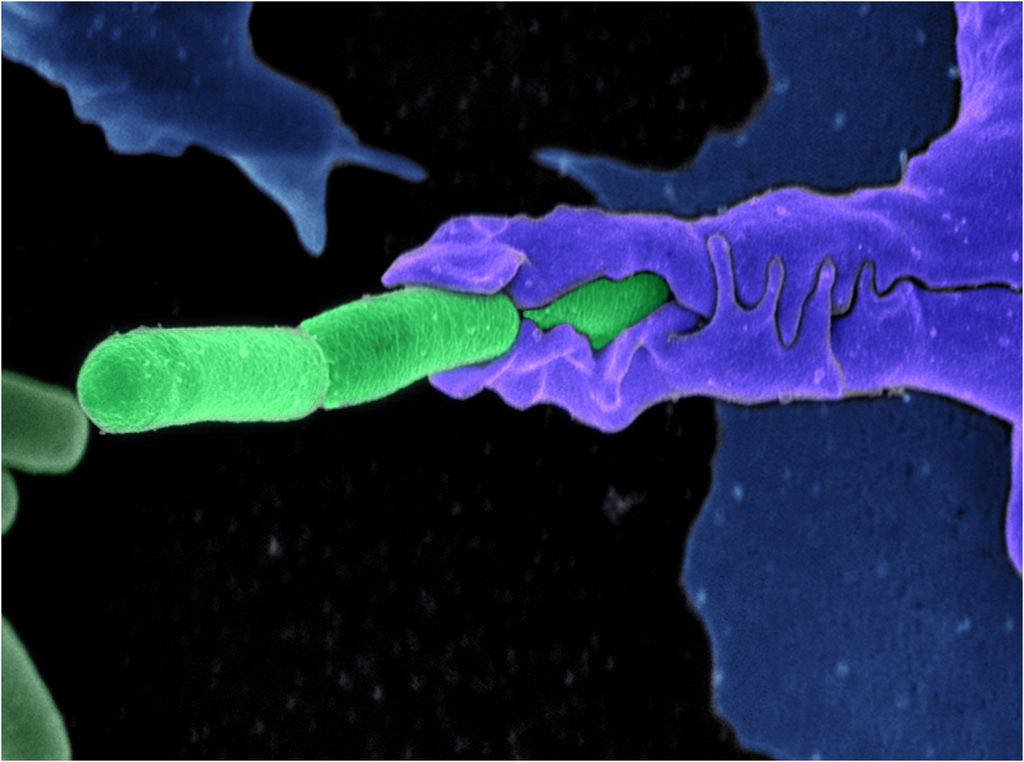

Read MoreHow to Prevent Illness by Boosting Your Immune System

Are you constantly suffering from colds and sniffles? Feeling run down and lethargic? Then it could be that your immune system is depressed. Matt has done some research and come up with some ideas on how to to help you.

Read MoreBeware of the Mom Taper

“Jodie can’t make training tonight because she is exhausted and worried about her homework deadlines”

A phone call, text or email late in the day from the Mum, and your plans for the night’s training session are scuppered. This is extremely frustrating as a coach. It happened to me 3 times last week alone.

A phone call, text or email late in the day from the Mum, and your plans for the night’s training session are scuppered. This is extremely frustrating as a coach. It happened to me 3 times last week alone.

Planning your Training: Periodisation for Young Athletes

What is Periodisation?

Periodisation is the term given to the practice of breaking down an athlete’s conditioning plan into specific phases of training.

Read MoreHave you got the 4 cornerstones of your training programme in place?

Any training programme for sport should consist of the following areas:

Preparation: Either planning, warming up, or getting ready to train.

Read MoreHow to Plan Your Training: GAIN Review 6

“90% of coaches’ work is grunt work” Terry Brand

Vern Gambetta did a few presentations on planning training, as well as a couple on coaching itself. The overall theme was “have a plan, then work the plan”. I will cover some specifics in this blog, as well as an overall summary.

Read MoreVladimir Issurin: Block Periodisation, UKSCA lecture.

Vladimir Issurin is a Coach with the Israeli Olympic Committee and Masters swimmer. His lecture compared traditional periodisation with block periodisation.

Vladimir Issurin is a Coach with the Israeli Olympic Committee and Masters swimmer. His lecture compared traditional periodisation with block periodisation.

He started by comparing training and competition days between 1980-1990 and from 1991-2000 across a variety of sports.

Read More