Posts Tagged ‘reflective practice’

GAIN Deep Dive Review

A review of the first ever GAIN Deep Dive on Foundational Strength I always write a review of my experiences at the GAIN conference. This is part of my reflective practice. As I was hosting and co-presenting on this ‘mini-GAIN’ held in Devon, I thought someone else would be better placed to reflect. Mark Sheppard…

Read MoreFour things I have learnt in 2019

I have learnt lots in 2019, but here are some of the key things. Some of them I should have known before, but have drifted away from or been blown off course. Thanks to all the members of Excelsior Athletic Development Club for helping me improve my coaching this year and inspiring me to try…

Read MoreFour takeaways from GAIN 2019

‘Make GAIN 2019 a personal audit’ were the opening remarks from Vern Gambetta at the GAIN conference in Houston last week. He set out a vision for the conference that I took to heart. What are you currently doing? What do you want/need to do? Gap analysis: what is necessary to close the gap? I…

Read MoreIFAC Reflections Part 2

A review of Jerome Simian’s workshops on physical preparation for sport. I had to choose between different “strands” of coaching topics at the IFAC conference in Loughborough. A difficult choice, not wanting to miss out on some excellent speakers. I chose to attend Simian’s because of a quote I heard on the HMMR podcast: “I…

Read MoreHow to Create Excellence In Coaching

For a start, I am not sure I have achieved this, but there are a few things that you can do to help make yourself and your coaching better.

Read More12 coaching lessons learnt in 2018

Things I think I have learnt this year 1.Athletes, especially young ones, have so much happening in their lives that our influence is minimal. Coaches need to realise this. 2. Periodisation planning is flawed in group settings in all but the most controlled environments (see #1). Every athlete doing your sessions has eaten, slept, socialised,…

Read MorePAR: Golf core values

Setting core values for your coaching environment Taking this golf example from Wade Gilbert’s “Coaching better every season” for coaches and players to help focus on what matters most. The golf coach ended up with the appropriate acronym PAR. Passion: Nurture love for the game of golf and competing. Achievement: Strive to achieve our competitive…

Read MoreUsing reflection and debriefs to enhance coaching: Wade Gilbert

“Why wait for a disaster to have a really open and frank conversation?” Wade Gilbert asked this at the GAIN conference in his presentation on reflection and debriefs for coaches. (This was two days after the Grenfell tower disaster where many people were asking the same thing). Wade said that systematic reflection could be the…

Read MoreCoaching Better Every Season: Wade Gilbert

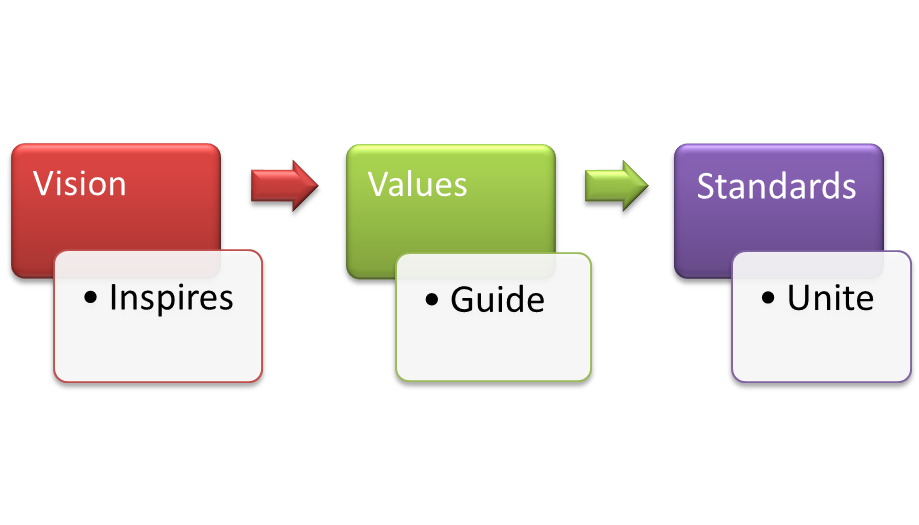

“If I want to get better, I need to know what better is.” Wade Gilbert gave an excellent overview of the coaching process and becoming a better coach at his GAIN seminar. This also served as an overview of his excellent book of the same name. His talk was split into 4 parts: Envision: Pre-season…

Read MoreGAIN 2017: Coaching reflections

I recently spent 5 days in Houston, Texas at Vern Gambetta’s GAIN conference. In this post, and those to follow, I shall attempt to share some of the main ideas and reflections gained whilst there. This should be of interest to fellow coaches and some to parents of athletes too. Opening address and overview by…

Read More