The oxymoronic Talent Pathway

Leave a CommentHow did people get good at sports before the existence of pathways and ‘talent’ academies?

If you read biographies of a previous generation of sporting superstars there is usually a mention of a dedicated p.e. teacher or coach at a local sports club. Children discovered their love for the sport locally and affordably. They might have had a keen parent, like Tim Henman or Seb Coe, but most stumbled into the sport through normal p.e. and games or by going with a friend to a local club.

The sport was fun, and well-coached and this lead to some successes and a desire to do a bit more training. There were no academies or pathways. ‘Sport for all’ was the Sport England motto.

This changed with the introduction of the National Lottery and the mechanisation of sport in the UK, especially after the ‘failure’ of Team GB at the Atlanta Olympics. Medal tables and podium places took the place of ‘Sport for all.’

Funding was dependent on National Governing Bodies (NGBs) meeting top-down objectives, including having a ‘pathway’ despite there being no evidence of such a thing working in reality. In his book, ‘The Talent Lab,’ Owen Slot summarises the report into Britain’s subsequent (and expensive) pursuit and attainment of medals thus,

‘There is no one single element of success, no one cap that fits all.’

The goal of UK sport was to win more Olympic medals and that was achieved: between the Atlanta Games and Rio (2016), GB won 96 medals.

However, just 12 people won or contributed to 49 of them.

Over half the medals were won by just a dozen individuals.

Or, to put it another way, is this a good use of public money?

Where is the Olympic Legacy?

In the ten years after the London Olympics, there has been a decrease in sporting participation. Part of that can be blamed on the Covid-pandemic and the various lockdowns. However, the pandemic may have hastened the decline rather than caused it.

There are two stark facts that should be first and foremost on the minds of parents, teachers, coaches and public health figures:

- Only 1 in 5 adolescents and adults meet the current weekly recommendations for aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercises for health across 31 countries.

- The reported levels of anxiety and depression in adolescent athletes in the USA are higher now than they were pre-Covid.

In other words, 80% of adolescents are not doing enough exercise to stay healthy.

Those that do play sports have more mental health issues than they did prior to Covid even though they have returned to activity.

And yet...

There are more ‘talent pathway managers’ than coaches in NGBs nowadays. More ‘scholarships’ and ‘academies’ and ‘talent programmes’ than there are minibuses to ferry the kids around. As soon as a child shows an interest (or an early growth spurt or specialisation) then they are ‘identified’ and told they ‘must’ attend a training/ selection camp miles away from home.

Those working within ‘Talent Pathways’ operate in an echo chamber where they attend conferences with other people in similar roles from different sports and share ‘best practice’ ideas! For those on an NGB salary, it is understandable that no one raises their hand and says,

‘Hold on! Shouldn’t we be focussed on helping young people get healthy and active and supporting them rather than cherry-picking from an ever-decreasing pool of participants?’

They would risk losing their job and their salary, so they stick to the company line.

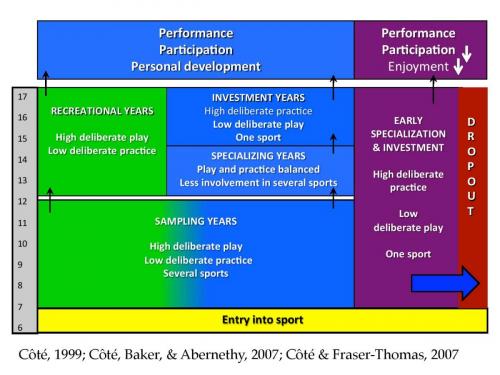

Too much, too early

NGBS are continuing to encourage young children to specialise, especially girls because they are afraid of losing ‘talent’ to another sport (see the Talent ID Bun Fight). They might not say so overtly, but when a child is told that they must attend weekly ‘talent’ sessions miles away and go to regular camps involving overnight stays, time and logistics prevent that child from doing anything else.

When I worked with England Golf, the regional (under-16 coaches) were told to:

1. Only select those girls who would definitely play for England at the senior level.

2. Select them at under 13 so they would ‘be in the system for longer.’

These young girls had barely started secondary school and they were put into the system. They were ill-equipped physically and emotionally for this intense training and expectation. Many of them quit the sport or just returned to their home coaches and courses.

The perverseness of the NGB means that the child is in danger of dropping out of all sports: burnout, injury, or competing demands such as schoolwork are the major causes.

The increased cost of fuel and a squeeze on family incomes means that even fewer children can afford to travel big distances, let alone afford overnight stays, to play sports.

And, it is worth repeating, there is no evidence that early selection at a young age leads to representation at a senior level: in fact, the opposite is often the case.

In German football, those playing in the National Team specialised later and played more ‘pick-up’ games with their friends than those just playing in the Bundesliga. The players who specialised earliest and had less ‘free-play’ ended up playing in semi-professional teams below the Bundesliga.

At some point, specialisation and more investment in training will be necessary: but it is at a later age than you think and only when the child is ready.

Playing a variety of sports, locally, with friends still works at a young age. If they are still sleeping with a teddy bear they should not be specialising.

Questions for parents to ask

Parents are bombarded with information from NGBs and often told that their child ‘has’ to be on the pathway in order to become successful. I suggest that parents ask the NGB the following questions:

1. Why?

2. Is there evidence that these ‘pathways’ work?

3. Can my child be successful without attending this academy?

4. Did any of the elite performers in your sport use a different route?

5. How much will it cost?

6. What happens if they are de-selected: will you help support them back at their club?

The answers that could be given are:

1. To show that the NGB is ‘doing something.’

2. Yes: for some people but not for all (as does every method). And there is a recency bias.

3. Yes: if given the right support and encouragement locally.

4. Yes, of course, they did. Some didn’t even start the sport until their late teens.

5. A lot: fuel, time, accommodation. Money that could be best spent elsewhere (unless you are wealthy).

6. No. The risk of dropping out entirely is high because the child perceives themselves as ‘a failure’ if they do not make the next set of teams.

Excelsior Athletic Development Club

Our club philosophy is to help every athlete get better. It is not to produce champions nor is it to be part of a ‘pathway.’ Every person has different motivations for training including:

· Goal/success driven

· Feeling fit and good about themselves.

· Looking good

· Hanging out with friends

· Learning a new skill.

All of these are valid and worthwhile. The problems only occur when there is a mismatch between their motivations for training and their willingness to train enough or if the coach’s expectations don’t match the athlete’s.

A goal-driven athlete who doesn’t want to train frequently will be frustrated when they don’t succeed.

The athlete who wants to feel fit and hang out with friends will be frustrated/ upset if the coach (me) tries to make them compete.

This comes down to communication and education. If our athletes can meet their expectations at our club they will continue to participate and see the benefits. This is led by them and facilitated by the coach.

It is not driven by an NGB setting targets.

We coach people at our club, not statistics. It is worthwhile remembering the old motto,

‘Sport for All,’ and helping the young generation along their journeys of discovery rather than forcing them into someone else’s pathway.

Said a concerned Mum at a recent workshop. She is far from alone. Talent identification has been misused by sports as an excuse for working kids too early and too hard.

Said a concerned Mum at a recent workshop. She is far from alone. Talent identification has been misused by sports as an excuse for working kids too early and too hard. Anyone on the Under 18s squad is supposed to sign up to the AASE programme which requires extra sessions in Bristol every week.

Anyone on the Under 18s squad is supposed to sign up to the AASE programme which requires extra sessions in Bristol every week.

Early participation is great, early specialisation less so.

Early participation is great, early specialisation less so.

This type of Talent ID testing is widely thought to be a Westernised adaptation of the methods used in the Eastern Bloc to select elite athletes.

This type of Talent ID testing is widely thought to be a Westernised adaptation of the methods used in the Eastern Bloc to select elite athletes.

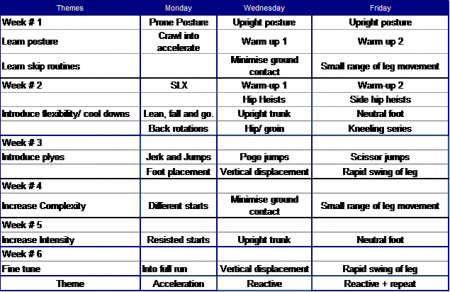

Acceleration:

Acceleration: A number of books have appeared recently in the USA and the UK purporting to explain the development of talent and excellence in the sporting and business environments. A common feature of these books is that they are written by journalists,who attempt to deal with complex scientific concepts.

A number of books have appeared recently in the USA and the UK purporting to explain the development of talent and excellence in the sporting and business environments. A common feature of these books is that they are written by journalists,who attempt to deal with complex scientific concepts. How can I get faster?

How can I get faster? All that learning can’t be good for you, so we finished the day with a Superstars style competition between 4 teams. The events worked on skill\ co ordination, teamwork, strength, and speed with skill. We finished with small sided football which was probably best described as “enthusiastic.”

All that learning can’t be good for you, so we finished the day with a Superstars style competition between 4 teams. The events worked on skill\ co ordination, teamwork, strength, and speed with skill. We finished with small sided football which was probably best described as “enthusiastic.”