The best weightlifting book: a review

1 CommentWhat are the best books to read about Olympic Weightlifting?

It depends on whether you are a lifter or a coach, and whether you are new or experienced. It might be that you are just interested to learn about the sport. You might be looking for technical information, or for a programme to follow. Here are 7 books I have recently read and used to some degree, it might help you choose the best weightlifting book

Skilful Weightlifting: John Lear. Paperback £7.95

I got this book from my coach Keith Morgan back in 2002 and I still refer to it now. The book starts off with a brief summary of the rules, what kit might be needed and then a section on biomechanics.

I got this book from my coach Keith Morgan back in 2002 and I still refer to it now. The book starts off with a brief summary of the rules, what kit might be needed and then a section on biomechanics.

It has very clear instructions on how to perform the lifts, with cues for each part of them. It gives advice for coaches on how to manage beginner lifters and what are the key areas to look out for.

There are clear diagrams and pictures throughout, which I find useful to show to my lifters (who are amused by the old school outfits). After the technical section, there is information on assistance exercises and how to fit them into your programme.

There is a section on programmes for 16-18-year-olds, more advanced lifters and also a 5 day a week programme for those who are unable to lift twice a day! This is clear information, set out in loads and sometimes %s. I would say that the youth programme lacks variation, which may be necessary to keep them interested and also to expose them to different aspects of the lifting.

However, this is a very good book, easy to read, contains enough relevant information, a great place to start.

The Weightlifting Encyclopedia: A Guide to World Class Performance. Arthur Drechsler paperback £30.88

A great book that was recommended to me by Ray Williams. It has 11 chapters and 4 appendices that cover just about everything you need to know about weight lifting ranging from technique to equipment to programming.

A great book that was recommended to me by Ray Williams. It has 11 chapters and 4 appendices that cover just about everything you need to know about weight lifting ranging from technique to equipment to programming.

More to the point, it is extremely well written. Dreschler draws on his own experiences and uses anecdotes to illustrate his points. When dispelling myths about ‘Secret Soviet methods’, he writes:

‘Exotic food supplements, restoration methods and plyometrics are just some examples of these supposed “secrets”. The results have been indigestion, lighter wallets and sore knees.‘

Dreschler analyses several different popular training systems and gives a fair account of what works in each and what is its downfall: pyramiding, circuit training, super sets, as well as those by popular coaches, Dan Hepburn, John Davis and Paul Anderson. This depth gives a great oversight and context for the information that follows.

There are detailed chapters on the classic lifts and a very good chapter on supplemental lifts and their relevance/ usefulness/transfer to the classic lifts. The section on competition preparation and cycling is good and then an excellent section on how to coach at a competition. There also chapters on dealing with injuries, psychological preparation and advice for the junior, female and masters weight lifter.

The highlight for me was the section on periodisation: Dreschler takes apart the classic periodisation model and the studies that advocate it. This book was written in 1998, but the advice about periodisation stands up now:

‘It is simple, easy and foolproof; to make an impressive plan, just pile on the volume and exercises during the preparatory period and cut things back during the competitive period, and you will have a plan that looks good on paper.‘

It is rare to see such a detailed book that is both readable, informative and practical as well as brimming full of research and applicable coaching philosophy in any sport. One of the best coaching books that I have read.

Olympic Style Weightlifting for the Beginner and Intermediate Weightlifter: Jim Schmitz paperback $16:95

This is basically a set of programmes for 1 year of training for those new to weightlifting, or returning from a layoff. The book’s strengths are its description of the assistance exercises and how the programme is laid out.

This is basically a set of programmes for 1 year of training for those new to weightlifting, or returning from a layoff. The book’s strengths are its description of the assistance exercises and how the programme is laid out.

It is designed around a 3 days a week programme, with each week being on one A4 page which is easy to follow in practice. This does mean that some of the sessions are quite long: over 90 minutes, so be prepared to spend some longer sessions in the gym.

It starts off with very simple programmes for the first 8 weeks, then progresses to the more varied programme which introduces different assistant exercises as well as increasing the load. In total there are 66 different exercises used.

The technical information is limited to a few paragraphs on the major lifts and the quality of the photos is poor. The layout of the book is functional to put it nicely but is basically photocopied sheets bound together.

This book is best for those who have an existing technical understanding of the lifts but want some idea of how to plan their year. It does that well.

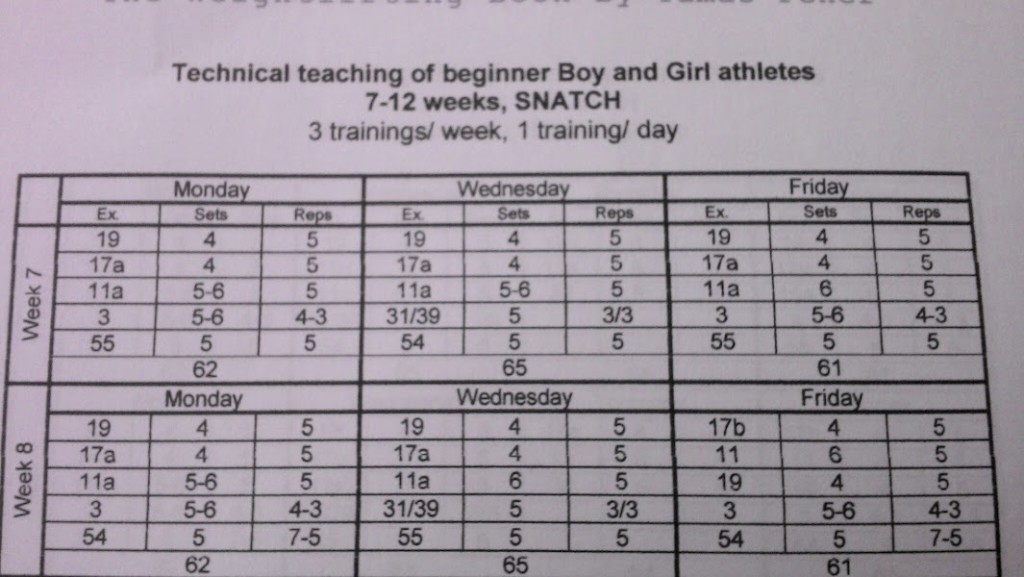

The Weightlifting Book; Tamas Feher pdf £29.95

This is a very technical book and covers more than just weightlifting. It looks at the overall coaching process as well as talent identification for WL. The book starts with detailed information on training methods, anatomy and physiology and then training processes.

It then moves to an in-depth analysis of the major lifts and their variations. This includes foot positions, hip and back angles and descriptions of how the different muscles are working at each phase. The accompanying pictures are clear but very small.

The next section is about strength development, followed by planning of loads and intensity, then overtraining and how to avoid it. These are well-written and in-depth. The sections on technical coaching for beginners, coaching philosophy and implementation are excellent.

The training planning and training programmes are more difficult to read. Feher is Hungarian, and they use a system where numbers replace the names of the exercises. This results in the programme looking like this:

In a normal book, it might be ok to flick backwards and forwards to see what you are doing, but in a pdf, it is just too laborious. The pdf format is the downfall of this book: I avoid screen time when not working, and carrying my laptop around in the gym is precarious. The other books I can just pull off a shelf and put in my bag, or keep them in the gym for reference. This one is strictly for reference only.

There is a dedicated section on coaching females and another one on the role of the coach. Both of these contain very useful information and philosophies. I am unable to comment on the efficacy of the programmes (Still waiting for Bletchley Park to crack the codes), but the detail of the information around them is excellent.

This book is strictly for coaches only.

Preparing for Competition Weightlifting: David Webster Paperback 1 penny.

This book is from 1986 by the then Scottish Coach. It has some useful technical points, with good illustrations in the opening section. This is the only place that I have seen a weightlifting coach advise that the double knee bend should be coached specifically. Every other WL coach I have met, trained with or read has said to avoid doing that (the UKSCA offers a different opinion, but they are not weightlifters).

This book is from 1986 by the then Scottish Coach. It has some useful technical points, with good illustrations in the opening section. This is the only place that I have seen a weightlifting coach advise that the double knee bend should be coached specifically. Every other WL coach I have met, trained with or read has said to avoid doing that (the UKSCA offers a different opinion, but they are not weightlifters).

Webster offers some useful insights into Eastern European and Soviet training methodologies: remember this was written before the fall of the Iron Curtain and YouTube. He also looks at annual planning and preparation. He borrows heavily from his friend John Jesse (Wrestling Physical Conditioning Encyclopedia) and so circuit-based training and interval runs feature prominently.

At 1 penny, how can you complain? But this book was strictly one of curiosity and historical context with a few useful points.

Weightlifting Programming A Winning Coach’s Guide: Bob Takano Paperback £20.92

(Thanks to Topsy Turner for the loan).

(Thanks to Topsy Turner for the loan).

A well-written, well-laid-out book that makes a huge difference to this reader’s experience. Takano offers a unique perspective at the beginning, looking at the Human Body and training systems from a Biology teacher’s viewpoint.

There is almost no technical information on the lifts in this book. Instead, it concentrates on how to develop programmes for different categories of lifters and explains the underlying rationale. The categories are:

- Class 3 (85kg lifter Total 170kg)

- Class 2 (85kg lifter Total 195kg)

- Class 1 (85kg lifter Total 225kg)

- Candidate for Master of Sport (85kg lifter Total 255kg)

- Master of Sport (85kg lifter Total 295kg)

- International Master of Sport (85kg lifter Total 365kg)

The 85kg male lifter gives you an idea of how the classes progress. Takano then devotes a chapter to the programming of each class, followed by a 20-week sample programme from his club athletes. This is very well laid out, easy to follow and well explained. I am unable to verify the efficacy of these programmes, having only class 3 lifters at our Weightlifting Club at present. But, I do like how the categories are subdivided beyond beginner, intermediate and advanced.

The chapter on regeneration is insightful, categorising the different types of restorative methods available. I think Tom Kurz in “Science of sports training” is the other book that covers this well. The nutrition section is very short and lacking in helpful real information, talking about macronutrients, rather than food.

The book finishes on the role of the coach and a call to action for coaches who want to improve what they do. Overall, it does what it says in the title, and it does it very well. One for club coaches I think, and a resource to use over time.

The Sport of Olympic-Style Weightlifting: Carl Miller with Kim Alderwick. Paperback £30

An A4 size book with 118 pages of text and charts, no images. The subtitle is “Training for the connoisseur“, It has an interesting start, looking at identifying different limb and torso ratios and giving advice on how to adjust the lifts accordingly.

Miller then briefly summarises Selye’s work on stress and adaptation, before devoting the next few chapters to training programmes. There is minimal technical advice here, just overviews of programmes and a list of exercises that should be included. This part of the book is weak and is done better elsewhere.

The last part of the book is based on weightlifting competition preparation including nutrition advice for making weight and mindset. This is better. I especially like this section on coaching at a competition:

“Any words should be simple and meaningful. Don’t clutter your mind with a lot of thought. You want a few cues that will allow things to happen automatically.

In the heat of the competition, only basic, familiar prompts are meaningful. The rest goes in one ear and out the other.”

Applies to every other sport too!

I got lent this by Topsy, but would have felt aggrieved at shelling out 30 quid for this. Guess I am no connoisseur!

Summary

These are the 7 books that I have read on the subject. If you have any further recommendations, then please comment below. For more technical information, I did enjoy reading Jim Schmitz’s series of articles here.

- Our Weightlifting Club is based in Willand, Devon. Please contact me if you are interested (details at the top of the page).

- Read more: Best books for sports coaches

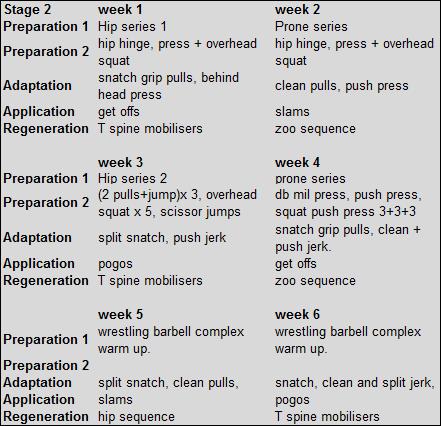

Here is the schedule for the next block of training for the Excelsior

Here is the schedule for the next block of training for the Excelsior

Guest post from Dave Leith of the Scottish Institute of Sport. I met Dave at the

Guest post from Dave Leith of the Scottish Institute of Sport. I met Dave at the A knowledgeable and experienced coach is essential!

A knowledgeable and experienced coach is essential! I try to begin lifting with new athletes under the conditions that we are working towards a competition. That means they need to develop resilient technique that will stand up to the competition conditions.

I try to begin lifting with new athletes under the conditions that we are working towards a competition. That means they need to develop resilient technique that will stand up to the competition conditions. Nick Garcia is one of the leading high school coaches in the U.S.A. For the past ten seasons he has served as the throwing coach at Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, California where he has guided more than thirty five throwers over 50-feet (15-metres).

Nick Garcia is one of the leading high school coaches in the U.S.A. For the past ten seasons he has served as the throwing coach at Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, California where he has guided more than thirty five throwers over 50-feet (15-metres). Each training Session begins with CEs. Basically a CE is the movement you perform in the competition itself. In the shot put it would be throwing with the rotational or glide techniques.

Each training Session begins with CEs. Basically a CE is the movement you perform in the competition itself. In the shot put it would be throwing with the rotational or glide techniques. While this category of exercise in general has higher transfer, I underlined particular thrower because each athlete is different. One athlete may have better transfer using heavy implements while another athlete may have better transfer with lighter implements.

While this category of exercise in general has higher transfer, I underlined particular thrower because each athlete is different. One athlete may have better transfer using heavy implements while another athlete may have better transfer with lighter implements.

Because the weight is lifted in 2 distinct movements, with a slight pause in between, heavier weights can be moved than in the snatch.

Because the weight is lifted in 2 distinct movements, with a slight pause in between, heavier weights can be moved than in the snatch. The Excelsior ADC

The Excelsior ADC  Flat shoes: For beginners, a pair of stout, stable, flat shoes is important. This creates a stable base upon which the lifts can be performed. Running shoes or (Heaven forbid) Vibram 5 fingers are unsuitable for weight lifting. (These handball shoes are a good choice for beginners’ weightlifting shoes.)

Flat shoes: For beginners, a pair of stout, stable, flat shoes is important. This creates a stable base upon which the lifts can be performed. Running shoes or (Heaven forbid) Vibram 5 fingers are unsuitable for weight lifting. (These handball shoes are a good choice for beginners’ weightlifting shoes.) Plasters/tape/nail clippers: at some point in your career as a weightlifter you will get blisters on your palms. This will happen sooner rather than later.

Plasters/tape/nail clippers: at some point in your career as a weightlifter you will get blisters on your palms. This will happen sooner rather than later.