Football training programme for under-18 player

5 CommentsNeeds Analysis of under- 18 football player

A guest post by Simon Worsnop, this study provides a needs analysis and periodised football training programme for an 18-year-old male academy fullback, based on the requirements of football and the individual.

A guest post by Simon Worsnop, this study provides a needs analysis and periodised football training programme for an 18-year-old male academy fullback, based on the requirements of football and the individual.

(This is a case study of a player that Simon coached. For football players in Devon and Somerset looking for a personalised training programme, in person, please see here ).

You can see an example of James coaching a footballer here

It accounts for his test scores and medical history. Although he has had no chronic injuries to date, he exhibits knee valgus on the rapid knee and hip flexion.

Table 1. Performance results of the case study athlete and normative data.

| Test | Case Study Player | Normative Data |

| Height | 1.79m | 179.3 Boone et al 2012

177.2 Sporis et al 2009 |

| Body Mass | 79kg | 73.4 Boone et al., 2012

74.5 Sporis et al 2009 |

| Body Fat % | 8.9 | 10.8 Rebelo et al., 2012

10.4 Boone et al., 2012 12.2 Sporis et al 2009 |

| VO2max test (Direct Gas Analysis on Treadmill) ml.kg.min-1 | 68 | 59.2 Sporis et al 2009,61.2 Vasilios and Kalapotharak 2011,61.2 Boone et al., 2012 |

| 5-Repetition Maximum Squat kg | 82.5 | 142.47 Comfort et al., 2014

149.3 Styles et al 2016 |

| Countermovement Jump | 35cm | 46.35 Comfort et al 2014,

38.6 Boone et al., 2012, 44.2 Sporis et al 2009, 40.2 Castagna et al 2013, 39.2 Arnason et al 2004, 37.0 Ingerbrightson et al 2013 |

| 5m Sprint Time s | 1.16 | 1.0 Comfort et al 2014

1.05 Styles et al 2016 1.43 Sporis et al 2009 |

| 10m Sprint Time s | 2.13 | 1.78 Styles et al 2016

1.93 Mendez-Villanueva et al., 2011 2.14 Sporis et al 2009 |

| 20m Sprint Time s | 3.30 | 3.00 Comfort et al 2014

3.05 Styles et al 2016 3.22 Manuel-Lopez et al., 2011 3.36 Sporis et al 2009 |

| Notes: Boone et al 2012 data on Elite Belgian Midfielders

Sporis et al 2009 data on Croatian 1st Division Mid Field Players Castagna et al 2013 U20 Italian national players Ingerbrightson et al 2013 Elite Danish 17-year-old players Comfort et al 2014 17-year-old English Academy players Squat Score is 1RM based on 5RM test Styles et al 2016 18-year-old British Academy players 1RM 90o Knee Angle Squat. |

||

The player is a fullback. He has two years’ strength and conditioning experience; training twice a week on a physical literacy programme. He is competent in the basic lifts including the front, back and overhead squats. He trains with a sub-elite league academy thrice weekly.

Table 2: Training Schedule

| 18.00 – 18.45 | 18.50 – 20.00 | 20.00 – 20.30 | |

| Monday | Weights | Technical/Tactical | Small-Sided Games |

| Wednesday | Weights | Technical/Tactical | Small-Sided Games |

| Friday | Speed & Plyometrics | Technical/Tactical | Small-Sided Games |

| Saturday | In Season: Match on most Saturday afternoons | ||

Introduction

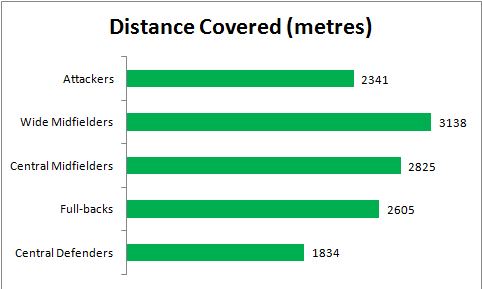

Football is a high-intensity aerobic game, with a player’s metabolic conditioning being crucial to his performance (Helgerud et al 2001). A Premier League full-back covers 10,730m in a game; 1,115m of this above 19km/h (defined as high-intensity distance) and 288m above 26.2km/h (defined as sprint distance), comprising a total of 68 sprints (Walker and Hawkins 2018).

Football is a high-intensity aerobic game, with a player’s metabolic conditioning being crucial to his performance (Helgerud et al 2001). A Premier League full-back covers 10,730m in a game; 1,115m of this above 19km/h (defined as high-intensity distance) and 288m above 26.2km/h (defined as sprint distance), comprising a total of 68 sprints (Walker and Hawkins 2018).

Players sprint every 90 seconds for a distance of between 1.5 m and 100m, with over 90% of these being less than 30 m (Bangsbo 1992), and almost half the sprints less than 10 m (Mirkov et al 2005). Because some of the sprints are from a rolling start or cover distances of over 60m maximum speed is important.

Sprints can often decide the outcome of a game, determining who gets to the ball first (Comfort et al 2014). A player changes direction every 2 to 4 seconds, a total of over 1200 within a game (Bangsbo 1992, Verheijen 1997) . Therefore, metabolic training should emphasise the repeatability of these high intense activities as opposed to long continuous running.

European soccer players miss on average 37/300 days through injury (Ehrmann et al 2016). Most injuries occurred in the lower extremities (82.9%), with the most common diagnosis being muscle/tendon injury (32.9%), especially hamstrings (13.3%) and groin (8.3%) (Stubbe et al 2015). One injury that can be career-threatening is an Anterior Cruciate Ligament rupture. Whilst these are high profile injuries, their occurrence is relatively low (0.43 per team per season) (Walden et al 2016). From both a player welfare perspective and in order to be able to select the best team any training programme should aim to reduce injury occurrence.

Player Needs Analysis

His anthropometric measurements are within the norms of elite soccer players (Carling et al 2010), body mass being towards the top of the range. Compared with the data in the table the player has a very good endurance level measured by his VO2max test. VO2max testing is done via a number of methods, which makes comparisons not ideal. Tests such as MSFT and YoYoIET have an acceleration and deceleration element which a treadmill test does not, possibly explaining the high score in this test. It is important not to get to “hung up” on VO2max scores as they do not always correlate with game-related fatigue (Hoffman et al 1999).

In comparison with normative data exhibited in Table 1 the player is deficient in speed, strength and power. His squat strength is well below that expected for a player of his status, and improving this must be the priority as this will have a positive effect on speed and power (Comfort et al 2014). Currently, his 5 Repetition Maximum (5RM) is 82.5kg which approximates to a 1RM of 92.75kg using the Brzycki Formula. This compares to scores of over 140kg in similar players in the works of Comfort et al., 2014, and Styles et al 2016. Squatting results are sometimes difficult to compare, some being based upon 5RM and others on 1RM, and differences of depth in various data, however even taking all this into account the difference in squat performance is huge.

Counter Movement Jump (CMJ) is a validated measure of power (Comfort et al 2014). The player’s CMJ scores are below those observed in similarly aged players; 10cm below English 17-year-olds (Comfort et al 2014), 5cm below Italian U20 (Castagna et al 2013) players and 2cm lower than Danish U17 players (Ingerbrightson et al 2013). These scores indicate a deficiency in power.

Counter Movement Jump (CMJ) is a validated measure of power (Comfort et al 2014). The player’s CMJ scores are below those observed in similarly aged players; 10cm below English 17-year-olds (Comfort et al 2014), 5cm below Italian U20 (Castagna et al 2013) players and 2cm lower than Danish U17 players (Ingerbrightson et al 2013). These scores indicate a deficiency in power.

The same can be said for his speed scores with his 5, 10 and 20-metre times all being considerably slower than similar scores. The speed tests from some European studies e.g., Sporis (2009) seem at odds with other results, this may be due to the reliability of the timing systems, starting procedures or running surface, therefore I have only considered those conducted most recently by British authors i.e., Comfort et al 2014 and Styles et al 2016.

An area of concern is the valgus movement of the knee during hip and knee flexion, which may significantly increase strain on the anterior cruciate ligament (Berns et al., 1992). This condition is often associated with weakness in the hip area, specifically the Gluteus medius (Hollman et al 2009).

This will be addressed in the programme, although “knee valgus means nothing if you don’t identify the cause” (Cook 2003 p 193). Proprioceptive/coordination training has been shown to reduce ankle injuries and better jumping and landing mechanics have been shown to decrease the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes (Junge and Dvorak 2004), and these should form part of the warm-up for field sessions. As stated earlier, there is a prevalence of groin and hamstring injuries within football and therefore exercises such as Nordics and Single Leg Stiff Leg Deadlifts are included in the strength programme with hip mobility and lateral lunges being part of the field warm-up (not discussed in this article but an example from James can be seen in this video).

Periodised Football Training Programme

Metabolic Training

Players with improved aerobic fitness covered greater distances, increased work intensity, the number of sprints and were involved in more “decisive” plays (Coutts 2005). Running velocity at Lactate Threshold is a key feature of football fitness (Ziogas 2011), therefore speed and anaerobic fitness are important. Fatigue may also lead to reduced skill accuracy and decision-making ability (Stone et al 2009), and therefore influence game outcome.

Players spend two-thirds of training at low intensities; however, only the time spent at a high intensity (>90%max HR) improves aerobic fitness (Castagna et al 2011). High-intensity interval training successfully improves aerobic fitness in a relatively short period of time and is an efficient training mode. Eight weeks of interval training increased VO2 max by 10.8 per cent, running velocity at lactate threshold by 13.1 per cent and increased running efficiency by 6.7 per cent (Helgerud et al 2001). Hoff and Helgerud 2004) used an intensity of 90 – 95 per cent of maximum heart rate (HRmax) for a duration of three to eight minutes, with recovery periods of 3 minutes at approximately 60-70 per cent HRmax.

Small-Sided Games (SSG) have beneficial results in football (Helgerud et al 2007); academy footballers using SSG improved performance equal to those following an aerobic interval training protocol (Reilly and White 2004), this protocol thus being an adequate substitute for physical training (Little and Williams 2006). Not all players achieve the same training results from SSG (Baker 2014). Players should be wearing Heart Rate Monitors and/or GPS to monitor the sessions. To provide bespoke metabolic training Maximal Aerobic Speed sessions could be implemented (Baker 2011).

Owen et al (2012) found a 4-week period of SSG did improve Repeat Sprint Ability (RSA) and Running Efficiency; however, Gabbett and Mulvey (2008) found SSG may not simulate high-intensity, repeated-sprint demands. (The Owen study has some serious design faults, and extrapolating the conclusions is questionable). RSA is often trained separately through position-specific pattern runs that include a high-level skill component (Walker and Hawkins 2018), as it may be poorly associated with Intermittent high-intensity endurance (Turner and Stewart 2014).

Many successful coaches integrate SSGs within a holistic tactical approach known as “tactical periodization” (Delgado-Bordonau, and Mendez-Villaneuva, 2012). If SSG are being used as the sole method of improving metabolic condition they should be periodized appropriately. Footballers must reach their peak in pre-season and maintain it through a long season (Turner and Stewart 2014). Therefore, the annual plan must reflect this.

Player numbers, pitch size and the presence of a goalkeeper affect physiological outcomes. Larger dimensions increase the aerobic demands (Casamichana and Castellano 2010, Rampinini et al 2007) but reduce the pressure of decision making; reducing field size increases decelerations, accelerations, direction changes and contacts with other players, and should not be introduced in phase 1 (Burgess 2014).

Thirty minutes of training time is allocated to small-sided games. Longer periods of work and larger player numbers are used early in the preseason. Players work more intensely in shorter interval periods; therefore, the rest periods are normally of approximately equivalent time. In larger sided games played for a longer time period, the rest period is relatively lower. When reducing rest periods it is important to monitor that players are able to maintain the required intensity. Low-intensity skill drills are used in the longer recovery periods (> 1 minute).

Friday’s session occurs when there is no game, therefore whilst the purpose is primarily metabolic conditioning, larger numbers (5 a side) are used to increase the tactical component and the numbers of high-velocity actions. Wednesday’s session is in addition to a match on a Saturday, therefore the numbers are smaller to increase the metabolic intensity, with less requirement for tactical stimulation (Turner and Stewart 2014). This is similar to the “intensive” and “extensive” approach (Walker and Hawkins 2018). Constraints in SSGs are adapted to achieve physical and tactical outcomes (Worsnop 2011); however here, for simplicity, equal numbers are used and it would be up to the coach on the day to manipulate these as required.

Speed and plyometric training are emphasised in Friday’s programme (not analysed in this article); so during the second phase, compared with Monday, SSGs with the smaller area will be used.

Table 3. Summary of Metabolic Periodisation.

| Phase | Player Numbers | Pitch Size | Interval Periods |

| 1 | Initially 7 v 7, including a goalkeeper reducing to 5 v 5 without a goalkeeper | 40 x 30 increasing to 60 x 40 | The larger sided games will be played for periods of between 4 & 8 minutes. The work time of the smaller sided games will progressively reduce as will the size of the pitch. This should shift the emphasis from aerobic conditioning with some longer sprints to anaerobic with more acceleration, turning and deceleration. |

| 2 | 3 v 3 on Friday

3 v 3 to 5 v 5 on Wednesday |

15 v 15 to 20 x 25

25 x 30 to 60 x 40 |

|

| 3 | Various dependent upon the available players, injury and fatigue status etc. A variety will be played within the week and in consecutive weeks rather than specific blocks. This form of concurrent periodization is more applicable to team sports and practically also avoids a player missing a whole stimulus block | ||

| 4 | |||

| 5 | |||

Strength Training Programme

In the Pre-season strength training will follow a classical periodization programme but in the competition phase an undulating approach (Poliquin, 1988).is used with volumes and intensities manipulated on a weekly and daily basis depending upon the playing schedule and the individual’s fatigue status (Turner and Stewart 2014).

Whilst there will be a greater emphasis on one strength quality within each mesocycle, there should always be some aspect of the others, especially the speed aspect that is so vital for success in football. Olympic Lifts are used to generate power (Hoffmann et al 2004). The player is competent in various squats, however, there is no mention of Olympic Lifts. Therefore, these have not been included, but simple dumbbell and barbell derivatives have been.

Squats are emphasized, as there are strong correlations with both absolute and relative squat strength and sprint and jumping performance in trained youth and adult soccer players (Comfort et al 2014). A twice-weekly 6-week in-season programme with one higher (4 x 5/85-90%) and one lower (3 x 3/85-90%) volume session showed moderate increases in absolute and relative strength and small but significant improvements in sprint time (Styles 2016). Some practitioners do not use back squats (Bosch 2015, Boyle 2010), but they are in a minority, ¾ of rugby conditioners regarding it as the most important exercise (Jones et al 2017), Some exercises are more suitable than others in developing power than maximum strength. Various weighted and unweighted jumps are extremely useful in developing power.

Table 4: Programme Summary

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Phase 5 | |

| Strength Endurance | Strength | Strength | Power | Power | |

| Day 1 | |||||

| Explosive | Clean High Pull From Floor | Clean Pull to Thigh | Single Arm Dumb Bell Snatch | Mid-Thigh Rack Pull | Jump Shrug |

| Squat Type | Front Squat | Front Squat | Back Squat | Concentric Box Jump | Back Squat + Drop Jump |

| Horizontal Press | DumbBell Incline Press

+ Dumb Bell Split Squat |

Incline Press | Bench Press | Smith Machine Bench Throws | VRT Bench Press |

| Vertical Pull | Pull-Ups

+ Dumb Bell Lateral Lunge |

Chin Ups | Wide Grip Pull Ups | Medicine Ball Slams | Chin Ups |

| Hip Bent | DumbBell Walking Lunge | ||||

| Rotational +/or Rehab | Dumb Bell Step Up +

Cable Wood Chop |

Nordic Raise | |||

| Day 2 | |||||

| Explosive | Snatch Pull From Floor | Snatch Pull From Thigh | Barbell CMJ | Single Arm Dumb Bell Snatch | |

| SL Squat | DumbBell Lunge + CMJ | Barbell Lunge | Back Squat | ||

| Vertical Press | Seated Dumb Bell Press + SB Leg Curl | Standing Dumb Bell Press | Military Press | Dumbbell Push Press | Dumbbell Push Jerk |

| Horizontal Pull | Standing Cable Row | Bent-Over Row | Seated Cable Row | Prone Row | SA Standing Cable Row |

| Hip Straight | KB SL SLDL | BB SL SLDL | TRX Leg Curl | Nordic Raise | KB SL SLDL |

| Rotational or Rehab | Nordic Raise | ||||

Rotational and Rehabilitation exercises will be added as the coach sees fit dependent upon the player’s status.

Phase 1 (Weeks 1 to 3)

Classically this is known as the hypertrophy phase, but more specifically it is strength endurance. Volume increases in preparation for what follows, using high repetition ranges, lower intensities and supersets. The primary aim is to increase tolerance to the demands being placed on the body and to address individual concerns via bespoke exercises. The number of exercises is greater than in subsequent phases and includes more unilateral exercises and different planes.

Specific to this player, split squats and step-ups will be included to work the gluteus muscles in a sport-specific way (Boyle 2010, Contreras 2009), and exercises for glute activation, e.g. mini-band walks and banded clams should be included during warm-ups (Walker and Hawkins 2018)

The programme must include horizontal and vertical push and pull exercises alongside adequate trunk training. There are a number of approaches to twice a week training, the one used offers a balanced approach, where the various exercise groups are spread over the two days. Where possible exercises within a preceding phase act as a preparation for the next.

Table 5 Phase 1 Strength Endurance Week (1 to 3)

| Monday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Clean High Pull From Floor | Front Squat | Dumbbell Incline Press

+ Dumbbell Split Squat |

Pull-Ups

+ Dumbbell Lateral Lunge |

Dumbbell Step-Up +

Cable Wood Chop |

| Week 1 | 3 x 12

40% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 12

60% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 12

45s between sets |

3 x 12

45s between sets |

3 x 12 each leg

45s between sets |

| Week 2 | 3 x 12

50% 1RM 60s between sets |

4 x 12

60% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 12 – 15

45s between sets |

3 x 12 -15

45s between sets |

3 x 12- 15 each leg

45s between sets |

| Week 3 | 3 x 12

60% 1RM 60s between sets |

4 x 12

70% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 12 – 15

45s between sets |

3 x 12 -15

45s between sets |

3 x 12- 15 each leg

45s between sets |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more but in this phase, you should have a “repetition to spare” working in good form, not to failure. For the other exercises choose weights that will allow you to work within the given rep’ range. Where there are two exercises these are carried with the second immediately following the first. Use assistance bands with the pull-ups if required | ||||

Front squats are used as they use less load than back squats. A clean high pull uses less load than a pull to the thigh and is appropriate to this phase. The super setting allows the volume to be added in various lower limb exercises to improve specific strength endurance.

Table 6 Phase 1 Strength Endurance (Week 1 to 3)

| Wednesday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Snatch Pull From Floor | DumbBell Lunge + CMJ | Seated Dumb Bell Press + Swiss Ball Leg Curl | Standing Cable Row | Kettlebell Single Leg Stiff Legged Deadlift | Nordic Raise |

| Week 1 | 3 x 12

40% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 12 el +10

45s between sets |

3 x 12 +12

45s between sets |

3 x 12

45s between sets |

3 x 12 each leg

45s between sets |

3 x 8 |

| Week 2 | 3 x 12

50% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 15 el+ 10

45s between sets |

3 x 12 – 15 +12

45s between sets |

3 x 12 -15

45s between sets |

3 x 12- 15 each leg

45s between sets |

3 x 12 |

| Week 3 | 3 x 12

60% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 15 el + 10

45s between sets |

3 x 12 – 15 + 12

45s between sets |

3 x 12 -15

45s between sets |

3 x 12- 15 each leg

45s between sets |

3 x 15 |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more but in this phase, you should have a “repetition to spare” working in good form, not to failure. For the other exercises choose weights that will allow you to work within the given rep’ range. Where there are two exercises these are carried with the second immediately following the first. Use assistance bands with the pull-ups if required For the Nordic Curls attach your feet under the feet hooks of a cable machine, use a band around your chest attached to the column so that you main control throughout the descent (Refer to the video on the Academy Facebook Page) | |||||

Specific details for Nordic curls are included as they are often poorly executed.

Table 7 Phase 2 Strength (Week 4 -6)

| Monday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Clean Pull to Thigh | Front Squat | Incline Press | Chin Ups | Nordic Raise |

| Week 4 | 3 x 5

75% -85% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 8

80% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 8

80% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 8 |

| Week 5 | 3 x 4

80 -90% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6

85% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6

85% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 12 |

| Week 6 | 3 x 3

85-95% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 15 |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more Make sure you have carried out any prehab before starting your programme and are fully warmed up and mobilized. Use 2 -3 warm-up sets prior to your work sets for the clean pulls and squats. Use weighted vests or belts for the chin-ups. For the Nordic use a lighter resistance band than in phase 1. | ||||

Clean pulls develop “strength speed”. The rest period, less than that used by competitive lifters is more appropriate for footballers.

Table 8 Phase 2 Strength (Week 4 -6)

| Wednesday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Snatch Pull From Thigh | Barbell Lunge | Standing Dumb Bell Press | Bent Over Row | BB Single Leg Stiff Leg DeadLift |

| Week 4 | 3 x 5

75% -80% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6 each leg

90s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 6 |

| Week 5 | 3 x 4

80-85%1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6 each leg

90s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 6 |

| Week 6 | 3 x 3

85-95% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4 each leg

90s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 6 |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more. Make sure you have carried out any prehab before starting your programme and are fully warmed up and mobilized. Use 2 -3 warm-up sets prior to your work sets for the snatch pulls and lunges. If you have any back soreness/fatigue substitute supported bent over dumbbell rows for the barbell row | ||||

The snatch pull from the thigh is used on the second day as it uses less weight. Lifts from the hang have a greater speed component than those from the floor.

Table 9 Phase 3 Strength (Weeks 7 – 12)

| Monday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Single Arm Dumb Bell Snatch | Back Squat | Bench Press | Wide Grip Pull Ups |

| Weeks 7 – 8 | 3 x 5

60s between sets |

3 x 5

85% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 8

80% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

| Weeks 9 – 10 | 3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6

85% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

| Week 11-12 | 3 x 3

60s between sets |

3 x 3

92%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more Make sure you have carried out any prehab before starting your programme and are fully warmed up and mobilized. Use 2 -3 warm-up sets prior to your work sets for the squats. Use weighted vests or belts for the pull-ups. | |||

Back squats use more weight than front squats providing greater neurological stimulation. Due to the extra stresses placed on the body by the back squat, single-arm dumbbell snatches are used as a power exercise as opposed to an Olympic barbell derivative.

Table 10 Phase 3 Strength (Weeks 7 – 12)

| Wednesday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Back Squat | Military Press | Seated Cable Row | TRX Leg Curl |

| Weeks 7 – 8 | 3 x 3

80% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 5

85% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 8

80% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

| Weeks 9 – 10 | 3 x 3

82%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 6

85% 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

| Weeks 11- 12 | 3 x 3

85% 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 3

92%+ 1RM 90s between sets |

3 x 4

90%+ 1RM 60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, if you are feeling stronger you may be able to add slightly more Make sure you have carried out any prehab before starting your programme and are fully warmed up and mobilized. Use 2 -3 warm-up sets prior to your work sets for the squats and military press. Maintain bridge position in TRX leg curl | |||

TRX curls are used as opposed to a traditional exercise such as the RDL to reduce the load on the back.

Table 11 Phase 4 Power (Week 13 – 18)

| Monday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Mid-Thigh Rack Pull | Concentric Box Jump | Smith Machine Bench Throws | Medicine Ball Slams |

| Week 13 – 14 | 3 x 5 70% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 5

90s between sets |

3 x 8 20% 1RM 60s between sets | 3 x 5 (use 10% of body weight)

60s between sets |

| Week 15- 16 | 3 x 4 75% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 4

90s between sets |

3 x 6 25% 1RM 60s between sets | 3 x 6

60s between sets |

| Week 17- 18 | 3 x 3 80% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 3

90s between sets |

3 x 4 30% 1RM 60s between sets | 3 x 4

60s between sets |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, do not be tempted to add extra weight to the bench throw as we aiming for speed of movement as well as speed of muscle contraction. For the box jumps aim to increase the height of the box each week. | |||

This session concentrates almost exclusively on power, with the rack pull also offering some strength stimulus. Bench throws load should be low in an inexperienced athlete (Baker 2001), velocity measurement would be useful.

Table 12 Phase 4 Power (Week 13 – 18)

| Wednesday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Barbell CMJ | Dumbbell Push Press | Prone Row | Nordic Raise |

| Week 13 – 14 | 3 x 5 25% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 5

90s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 8 |

| Week 15- 16 | 3 x 4 30% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 4

90s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 12 |

| Week 17- 18 | 3 x 3 35% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 3

90s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 15 |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, do not be tempted to add extra weight to the CMJ as we aiming for speed of movement as well as speed of muscle contraction. For the Nordic Raise choose an appropriate resistance band if required. | |||

Dumbbell Push Presses and supported rows are used in case of residual fatigue from the long season. CMJ load should be low in an inexperienced athlete (Baker 2001), velocity measurement would be useful.

Table 13 Phase 5 Power (Week 19 – 24)

| Monday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Jump Shrug | Back Squat + Drop Jump | VRT Bench Press | Chin Ups |

| Week 19 – 20 | 3 x 5 30% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 5 (75%) + 5

60s between squat and jump and subsequent squat |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

| Week 21- 22 | 3 x 4 35% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 4 (80%) + 5

60s between squat and jump and subsequent squat |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

| Week 23- 24 | 3 x 3 40% 1RM

60s between sets |

3 x 3 (85%) + 5

60s between squat and jump and subsequent squat |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

| Notes | On major exercises work to the percentages 1RM given, do not be tempted to add extra weight as we aiming for speed of movement as well as the speed of muscle contraction. For the drop jumps aim to increase the height of the box each week (you will be given the exact depths to work from). Use 20% load from elastic bands for VRT Bench Press | |||

Back squats are re-introduced, otherwise, the player would not squat for over 12 weeks. The load is a compromise between providing enough stimulus and not inducing fatigue. Jump Shrugs are used as the power exercise, with the emphasis on the speed part of the speed-strength curve. Variable Resistance Training is included as it improves speed strength in academy age athletes (Rivie`re.2017).

Table 14 Phase 5 Power (Week 19 – 24)

| Wednesday

18.30 – 19.15 |

Single Arm Dumb Bell Snatch | Dumbbell Push Jerk | Single Arm Standing Cable Row | Kettlebell Single Leg Stiff Leg DeadLift |

| Week 19 – 20 | 3 x 5

60s between sets |

3 x 5

60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

3 x 8

60s between sets |

| Week 21- 22 | 3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

3 x 6

60s between sets |

| Week 23- 24 | 3 x 3

60s between sets |

3 x 3

60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

3 x 4

60s between sets |

| Notes | Make sure you work on scapula retraction during the cable row. | |||

Single limb exercises are used on “day 2”, to reduce the risk of fatigue when using a heavier barbell alternative, and emphasising the speed element of power.

Metabolic Conditioning

Table 15 Phase 1 (Week 1 – 3)

| Wednesday | Friday | |

| Week 1 | 7 v 7 including goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 3 x 8 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

6 v 6 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 x 6 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 2 | 6 v 6 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 x 6 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 5 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 3 | 6 v 6 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 x 6 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 6 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

Table 16 Phase 2 (Week 4 – 6)

| Wednesday | Friday | |

| Week 4 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

3 v 3 no goalkeeper

Pitch Size 25 x 20 4 v 4 minutes 4 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 5 | 4 v 4 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

3 v 3 no goalkeeper

Pitch Size 20 x 15 5 v 3 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 6 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery between sets 1 & 2 and 2 & 3, 2 minutes light skills between sets 3 & 4 (Do not tell players about the reduced rest period, note how they react mentally and physically) |

3 v 3 no goalkeeper

Pitch Size 15 x 15 6 v 2.5 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

Table 17 Phase 3 (Week 7 – 12)

| Wednesday | Friday | |

| Week 7 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 8 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 6 x 2.5 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 9 | 4 v 4 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 10 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 (2 x (4 x 2) minutes) 1 minute recovery between reps 2 minutes between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 11 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 5 v 4 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 12 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 2 x (4 x 2) minutes) 1 minute recovery between reps 2 minutes between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

Table 18 Phase 4 (Week 13 – 18)

| Wednesday | Friday | |

| Week 13 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 14 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 6 x 2 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 15 | 4 v 4 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 16 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 6 x 2 minutes 1.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 17 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 x 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 18 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 8 x 2 minutes 1.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

Table 19 Phase 5 (Week 19 – 24)

| Wednesday | Friday | |

| Week 19 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 20 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 6 v 2.5 minutes 2 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 21 | 4 v 4 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 22 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 (2 x (4 x 2) minutes) 1 minute recovery between reps 2 minutes between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 23 | 5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 5 v 4 minutes 2.5 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 50 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

| Week 24 | 3 v 3 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 40 x 30 2 x (4 x 2) minutes 1 minute recovery between reps 2 minutes between sets |

5 v 5 no goalkeeper.

Pitch Size 60 x 40 4 v 4 minutes 3 minutes light skills drills as recovery |

Useful Resources

Gambetta Vern (2007) Athletic Development, The Art and Science of Functional Sports Conditioning Human Kinetics Champaign Ill

Strudwick Tony (2016) (Editor) Soccer Science, Using Science to Develop Players and Teams Human Kinetics Champaign Ill

References

- Arnason A, Sigurdsson SB, Gudmundsson A, Holme I, Engebretsen L, and Bahr R. 2004 Physical fitness, injuries, and team performance in soccer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 278–285,.

- Baker, D. 2001 Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 15(2):198-209,

- Baker D 2011 Recent trends in high- intensity aerobic training for field sports UKSCA Journal Issue 22

- Baker D 2014 High Powered Workshops Presentation 5 Current Trends in Endurance Training for Field, Court and Short Duration athletes. Workshop Sheffield 2014

- Bangsbo J. 1992 Time and motion characteristics of competition soccer. In: Science Football (Vol. 6),. pp. 34–40

- Berns G S, Hull M L, Paterson H A. 1992. Strain in the anteriormedial bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament under combined loading. J Orthop Res 10167–176.

- Boone, J, Vaeyens, R, Steyaert, A, Vanden Bossche, L, and Bourgois, 2012 J. Physical fitness of elite Belgian soccer players by player position. J Strength Cond Res 26(8): 2051–2057,

- Bosch, F. 2015 Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach Uitgevers Rotterdam

- Boyle, M. 2010 Advances in Functional Training: Training Techniques for Coaches, Personal Trainers and Athletes On Target Publications Santa Cruz CA

- Burgess, D. 2014 Optimising Pre-Season Training in Team sports in Joyce, D, and Lewindon, D. High Performance Training for Team Sports Human Kinetics Champaign Ill

- Carling, C and Orhant, E. 2010 Variation in body composition in professional soccer players: interseasonal and intraseasonal changes and the effects of exposure time and player position. J Strength Cond Res 24(5): 1332-1339,

- Casamichana D and Castellano J. 2010 Time motion, heart rate, perceptual and motor behaviour demands in small-sided games: Effects of field size. J Sports Sci 28: 1615– 1623, 2010.

- Castagna, C and Castellini, E. 2013 Vertical jump performance in Italian male and female national team soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 27(4): 1156–1161,

- Castagna, C, Impellizzeri, FM, Chaouachi, A, Bordon, C, and Manzi, V. 2011. Effect of training intensity distribution on aerobic fitness variables in elite soccer players: A case study. J Strength Cond Res 25: 66–71,

- Comfort, P., Haigh, A. and Matthews, M. J. 2012 ‘Are changes in maximal squat strength during preseason training reflected in changes in sprint performance in football players?’ J Strength Cond Res, 26: pp. 772-776.

- Comfort, P, Stewart, A, Bloom, L, and Clarkson, B. 2014 Relationships between strength, sprint, and jump performance in well-trained youth soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 28(1): 173–177

- Contreras, B 2009. Advanced Techniques in Glutei Maximi Strengthening ebook

- Cook G 2003 Athletic Body in Balance: Optmal movement skills and conditioning for performance Human Kinetics Champaign Ill

- Coutts, A. 2005 Training aerobic capacity for improved performance in team sports Sports Coach 27 4

- Delgado-Bordonau, J, L, and Mendez-Villaneuva, A 2012 Tactical Periodization: Mourinho’s Best Kept Secret Soccer Journal May/June 2012 p29 -34

- Ehrmann, FE, Duncan, CS, Sindhusake, D, Franzsen, WN, and Greene, DA. 2016 GPS and injury prevention in professional soccer. J Strength Cond Res 30(2): 360–367,

- Gabbett, T, J and Mulvey, M, J. 2008 Time and Motion Analysis of Small-Sided Training Games and Competition in Elite Women Soccer Players Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(2), 543-552.

- Helgerud J, Hoydal K, Wang E, Karlsen T, Berg P, Bjerkaas M, Simonsen T, Helgesen C, Hjoth N, Bach R, and Hoff J. 2007 Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2max more than moderate training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 665–671,.

- Helgerud J, Engen L, Wisloff U, and Hoff J. 2001 Aerobic endurance training improves soccer performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 1925–1931,.

- Hoff, J, and Helgerud, J. 2004 “Endurance and strength training for soccer players” Sports Medicine, 34(3): 165-80.

- Hoffman, J.R., J. Cooper, M. Wendell, and J. Kang. 2004 Comparison of olympic versus traditional power lifting training programs in football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18(1):129– 135.

- Hoffman J R.; Epstein S; Einbinder, M; Weinstein, Y 1999 The influence of aerobic capacity on anaerobic performance and recovery indices in basketball players Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 13:407-411

- Hollman J.H, Ginos B,E, Kozuchowski J, Vaughn A,S, Krause D,A, Youdas J,W. 2009 Relationships between Knee Valgus, Hip-Muscle Strength, and Hip- Muscle Recruitment During a Single-Limb Step-Down. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. 18: 104-117.

- Ingebrigtsen, J, Shalfawi, SAI, Tønnessen, E, Krustrup, P, and Holtermann, A. 3013 Performance effects of 6 weeks of aerobic production training in junior elite soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 27(7): 1861–1867,

- Jones, TW, Smith, A, Macnaughton, LS, and French, DN. 2017 Variances in strength and conditioning practice in elite Rugby Union between the Northern and Southern hemispheres. J Strength Cond Res 31(12): 3358–3371,

- Junge A and Dvorak J. 2004 Soccer injuries: A review on incidence and prevention. Sports Med 34: 929–938

- Little, T, and Williams, A. 2006 Suitability of soccer training drills for endurance training Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 20(2), 316-319)

- Manuel-Lopez, S., Marques, C. M., Roland, V. D. T. and Gonzalez-Badillo, J. 2011 ‘Relationships between Vertical Jump and Full Squat Power Outputs with Sprint Times in U21 Soccer Players’. Journal of Human Kinetics: 135 – 144. DOI:10.2478/v10078-011-0081-2.

- Mendez-Villanueva A., Buchheit, M., Kuitunen, S., Douglas, A., Peltola, E. and Bourdon, P. 2011 ‘Age-related differences in acceleration, maximum running speed, and repeated-sprint performance in young soccer players’. Journal Sports Science, 29: 477-484.

- Mirkov D, Nedeljkovic A, Kukolj M, Ugarkovic D, and Jaric S. 2008 Evaluation of the reliability of soccer-specific field tests. J Strength Cond Res 22: 1046–1050,.

- Owen, AL, Wong, DP, Paul, D, and Dellal, A. 2012 Effects of a periodized small-sided game training intervention on physical performance in elite professional soccer. J Strength Cond Res 26(10): 2748–2754,

- Poliquin, C, 1988 Five ways to increase the effectiveness of your strength training program. NSCA Journal 10(3):34-39

- Rampinini E, Impellizzerri FM, Castagna C, Abt G, Chamari K, Sassi A, and Marcora SM. 2007 Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided games. J Sports Sci 25: 650–666,.

- Rebello, A. et al. 2012 ‘Anthropometric Characteristics, Physical Fitness and Technical Performance of Under-19 Soccer Players by Competitive Level and Field Position’. Internal Journal Sports Medicine, 34(4): pp. 312-317.

- Reilly, T, and White, C. 2004 Small sided games as an alternative to interval training for soccer players J Sports Sci 22:559

- Rivie`re, M, Louit, L, Strokosch, A, and Seitz, LB. 2017 Variable resistance training promotes greater strength and power adaptations than traditional resistance training in elite youth rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res 31(4): 947–955,

- Sporis G, Jukic I, Ostojic SM, and Milanovic D. 2009 Fitness profiling in soccer: Physical and physiologic characteristics of elite players. J Strength Cond Res 23: 1947–1953

- Stolen TK, Chamari C, Castagna C, and Wisloff U. 2005 Physiology of soccer: An update. Sports Med 35: 501–536.

- Stone K, L, and Oliver, J,L, 2009 The effect of 45 minutes of soccer-specific exercise on the performance of soccer skills. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 4 163 -175.

- Stubbe, J. H., van Beijsterveldt, A.-M. M. C., van der Knaap, S., Stege, J., Verhagen, E. A., van Mechelen, W., & Backx, F. J. G. 2015. Injuries in Professional Male Soccer Players in the Netherlands: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Athletic Training, 50(2), 211–216. http://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.64

- Styles, WJ, Matthews, MJ, and Comfort, P.2016 Effects of strength training on squat and sprint performance in soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 30(6): 1534–1539, 2016—

- Turner, A, and Stewart, P,F, 2014 Strength and Conditioning for Soccer Players Journal of Strength and Conditioning 36 (4) p1 – 13

- Verheijen R. Handbuch fur Fussballkondition. Leer, Germany: BPF Versand. 1997.

- Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, et al 2016 ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture Br J Sports Med;50:744-750.

- Walker, G, J, and Hawkins, R. 2018 Structuring a Program in Elite Professional Soccer Journal of Strength and Conditioning 40 (3) p72-82

- Worsnop, S 2011 Rugby Games and Drills Human Kinetics Champaign Ill

- Ziogas, GG, Patras, KN, Stergiou, N, and Georgoulis, AD. 2011 Velocity at lactate threshold and running economy must also be considered along with maximal oxygen uptake when testing elite soccer players during preseason. J Strength Cond Res 25(2): 414–419.

Before trying to increase the quantity of high intensity work in training, it is first necessary to train the quality of speed.

Before trying to increase the quantity of high intensity work in training, it is first necessary to train the quality of speed. trauma after the war.

trauma after the war.

See our Run Faster programme

See our Run Faster programme

The ability to run fast in a straight line can be broken down into two components:

The ability to run fast in a straight line can be broken down into two components: Pre-season training is the optimal time to begin working on speed and running technique as players are generally fresh after a few weeks off post-season.

Pre-season training is the optimal time to begin working on speed and running technique as players are generally fresh after a few weeks off post-season. llen is the clinical director of the

llen is the clinical director of the  All this led into the type of injuries the dancers have: medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) is very common and the males have more thoracic back injuries (due to lifting females) and the females have more facet joint injuries in the lumbar spine. The

All this led into the type of injuries the dancers have: medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) is very common and the males have more thoracic back injuries (due to lifting females) and the females have more facet joint injuries in the lumbar spine. The

The mouth guard claims to work by properly aligning and relaxing the muscles in the face and jaw which may improve strength and balance. Theoretically it has been suggested that jaw position may affect posture and stability in individuals.

The mouth guard claims to work by properly aligning and relaxing the muscles in the face and jaw which may improve strength and balance. Theoretically it has been suggested that jaw position may affect posture and stability in individuals. With contradicting and lack of scientific evidence it is crucial to question the validity and theory of jaw alignment actually effecting performance. Is it worth the £1000+ it costs?

With contradicting and lack of scientific evidence it is crucial to question the validity and theory of jaw alignment actually effecting performance. Is it worth the £1000+ it costs?