Posts Tagged ‘GAIN’

GAIN Deep Dive Review

A review of the first ever GAIN Deep Dive on Foundational Strength I always write a review of my experiences at the GAIN conference. This is part of my reflective practice. As I was hosting and co-presenting on this ‘mini-GAIN’ held in Devon, I thought someone else would be better placed to reflect. Mark Sheppard…

Read MoreFour takeaways from GAIN 2019

‘Make GAIN 2019 a personal audit’ were the opening remarks from Vern Gambetta at the GAIN conference in Houston last week. He set out a vision for the conference that I took to heart. What are you currently doing? What do you want/need to do? Gap analysis: what is necessary to close the gap? I…

Read MoreSports Science for sports coaches

Sports Science for coaches Last month I attended Vern Gambetta’s GAIN conference in Houston, Texas. A great mix of practical sessions, seminars and informal idea sharing, it is my annual chance to take time out and immerse myself in learning. I shall be sharing some of the ideas and insights learnt this year. The act…

Read MoreLTAD: building young people

Using reflection and debriefs to enhance coaching: Wade Gilbert

“Why wait for a disaster to have a really open and frank conversation?” Wade Gilbert asked this at the GAIN conference in his presentation on reflection and debriefs for coaches. (This was two days after the Grenfell tower disaster where many people were asking the same thing). Wade said that systematic reflection could be the…

Read MoreCreating the Perfect Workout: Vern Gambetta and Jim Radcliffe

“We should warm up with skills not drills” Said Jim Radcliffe in his joint presentation with Vern Gambetta at GAIN. Combined they have been on an 89 year journey and “We can do better” said Vern in trying to create the perfect workout. This was an interesting dual presentation with a lot of back and…

Read MoreDeveloping the Robust Athlete: Jim Radcliffe

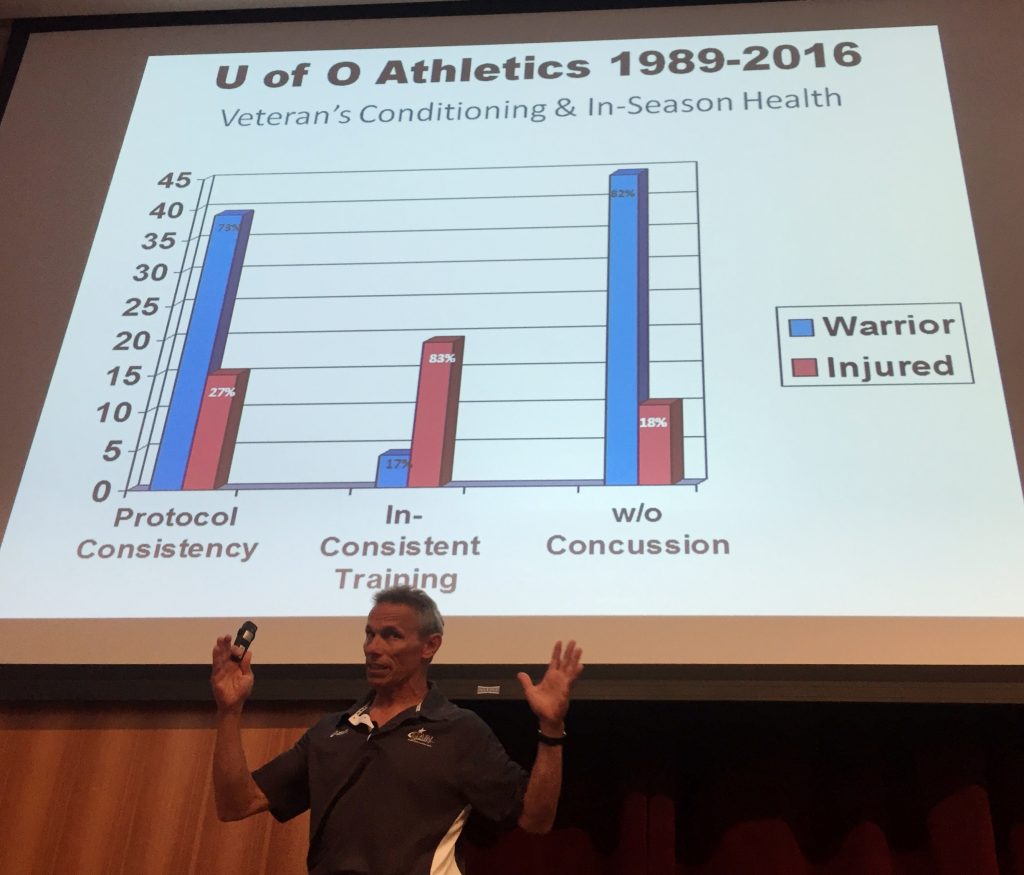

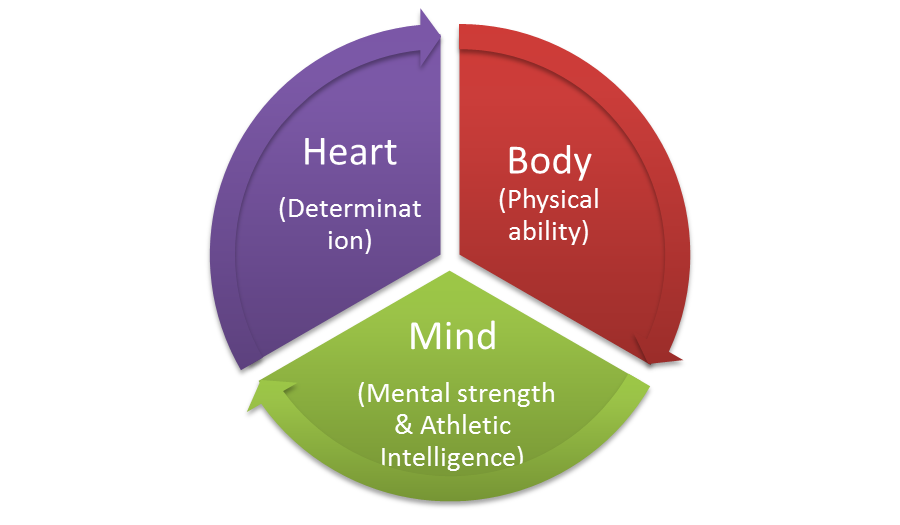

“Some people can negotiate the speed bumps of life, some end up in a ditch.” Jim Radcliffe talking about the Robust Athlete in his excellent presentation at GAIN this year. Jim has coached at The University of Oregon since 1989 and has been a major influence on my coaching since 2011 when I first saw…

Read MoreCoaching Better Every Season: Wade Gilbert

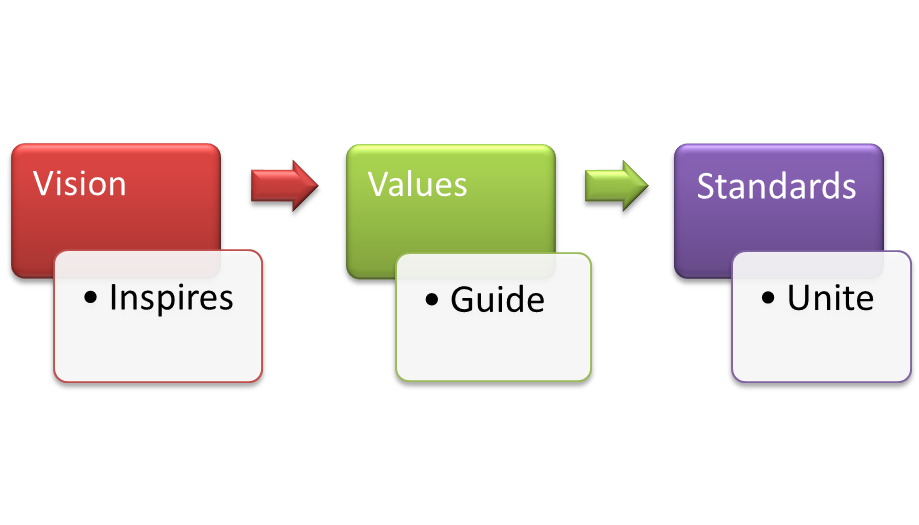

“If I want to get better, I need to know what better is.” Wade Gilbert gave an excellent overview of the coaching process and becoming a better coach at his GAIN seminar. This also served as an overview of his excellent book of the same name. His talk was split into 4 parts: Envision: Pre-season…

Read MoreApplying the Bondarchuk Method of Training: Martin Bingisser

Systematic Planning for Your Athletes Developing a plan for your athletes can be problematic, time consuming and potentially useless. Martin Bingisser gave some very useful tips in his GAIN presentation which will help coaches looking to develop a system. Martin is an advocate of the Bondarchuk system of training which uses a limited sequence of…

Read MoreHelping your child become happy and active within sport

“Youth sports is a business plan that fluffs egos and packs pocket books” Said Randy Ballard of Illinois University at the GAIN conference in Houston last month. He was talking about how parents try to get their children to specialise in sport too early, without realising the dangers of this. “75% of kids quit sports…

Read More

“What is LTAD?” has been demoted to a project question for students, a scientific discussion, or a pdf issued by National Governing Bodies (NGBs).

“What is LTAD?” has been demoted to a project question for students, a scientific discussion, or a pdf issued by National Governing Bodies (NGBs).