Posts Tagged ‘plyometrics’

How to develop speed: Gary Winckler

“The hamstrings transfer force from the motor of the butt to the wheels of the foot.”

Tenets of speed development

Athletics coach Gary Winckler delivered an excellent overview on what he thinks is important on developing speed. A lot of the work is similar to what Frans Bosch did a couple of years ago, and he mentioned Bosch’s work a lot.

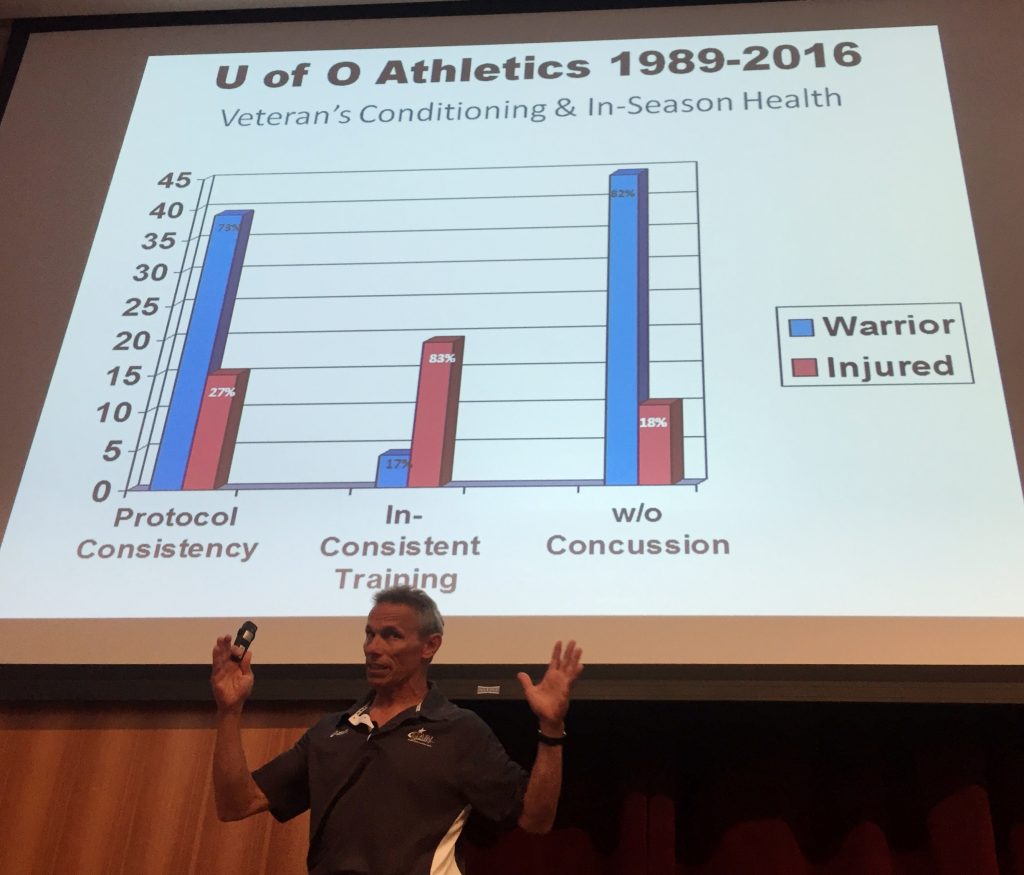

Read MoreDeveloping the Robust Athlete: Jim Radcliffe

“Some people can negotiate the speed bumps of life, some end up in a ditch.” Jim Radcliffe talking about the Robust Athlete in his excellent presentation at GAIN this year. Jim has coached at The University of Oregon since 1989 and has been a major influence on my coaching since 2011 when I first saw…

Read MorePlyometrics and Agility: Jim Radcliffe

“Try to be more like a super ball not a tomato”

Jim Radcliffe’s advice on plyometric training rang true as he went through a series of progressions for plyometrics.

Jim Radcliffe’s advice on plyometric training rang true as he went through a series of progressions for plyometrics.

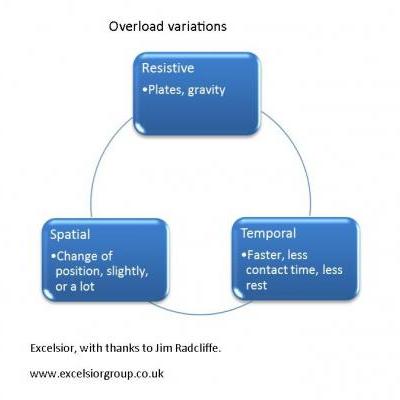

Principles of Training: Overload variations

“If your only tool is a hammer, then everything becomes a nail”

If your only way of overloading an athlete to cause adaptation is adding weight, then you are limiting what they can achieve.

Not every sport, or every athlete needs to be loaded in the same way. One way of defining overload (as I learnt from Jim Radcliffe on GAIN 2011) is shown here:

Read MoreStrength and conditioning for basketball: some thoughts.

If you think that basketball conditioning should resemble a scene from Coach Carter with repeated running in straight lines, you might be mistaken.

I am lucky enough to train some good young basketball players. Most of them arrive with some sort of work ethic and overall athleticism.

I am lucky enough to train some good young basketball players. Most of them arrive with some sort of work ethic and overall athleticism.

Is it the shoes? 3 tips to improve your vertical jump.

Basketball players looooove their shoes. Even NBA players have succumbed to the allure of shiny new shoes that claim to improve your vertical jump. But more than shoes, there are some simple ways of improving your vertical jump (or Vertical in the basketball vernacular). Get stronger legs. Sounds simple, but improving your overall leg strength…

Read MoreAgility with a Purpose: Jim Radcliffe

Posture, Balance, Stability, Mobility

These are the 4 key points that Jim Radcliffe keeps coming back to when he discusses his agility periodisation and planning.

These are the 4 key points that Jim Radcliffe keeps coming back to when he discusses his agility periodisation and planning.

His lecture and practical sessions at GAIN V expanded on the work he did last year (detail here).

Read MoreStrength and Conditioning: Putting the Athlete first.

3 weeks ago I went to Houston for GAINV, a conference for Athletic Development Coaches, Strength and Conditioning coaches, Physical Education Teachers, Athletic Trainers, Physiotherapists, Track and Field Coaches and various other professions.

3 weeks ago I went to Houston for GAINV, a conference for Athletic Development Coaches, Strength and Conditioning coaches, Physical Education Teachers, Athletic Trainers, Physiotherapists, Track and Field Coaches and various other professions.

Run by Vern Gambetta, it was an intensive 5 days of learning in the classroom, on the track and in the gym. The theme was “Coaching” and it was a masterclass in how to organise an event and share information and ideas.

Read MoreHow to Plan Your Training: GAIN Review 6

“90% of coaches’ work is grunt work” Terry Brand

Vern Gambetta did a few presentations on planning training, as well as a couple on coaching itself. The overall theme was “have a plan, then work the plan”. I will cover some specifics in this blog, as well as an overall summary.

Read MorePower, acceleration and force: GAIN review 5

“Some research can’t interpret it’s own data, sometimes that data is wrong.”

Jack Blatherwick opened my eyes with 2 great lectures. The first was on Acceleration, the second on research. He had some great visual slides, that just explained things very clearly. There was a constant sound of “oh, I see….” From around the room as people began to grasp hitherto poorly understood subjects.

Not sure I can do it justice…

Read More