Main Menu

Latest Blog Entry

User login

What the academics are keeping from the public

“The average number of readers of a scientific paper is…”

(Answer at the bottom of the page). Sir Martin Rees in his book “Before the beginning: our universe and others” discusses science, evidence and why information fails to get through to the public

University undergraduates are told by their lecturers that they must reference academic journals and that they need to be current. Books are less relevant as they are “out of date”. Naseem Taleb in “Antifragile” (a book) calls this “neomania“: the obsession with something new.

Rees has this to say about journals:

“But these journals- what scientists call ‘the literature’– are impenetrable to non-specialists. They now just exist for archival purposes, largely unread even by researchers, who depend more on informal ‘reprints’, email and conference.”

Does that ring a bell for coaches who are wading through articles?

Information distortion

In the age of the tweet, the soundbite and 24 hr rolling news coverage, Rees explains that information can get distorted. Ben Goldacre talks about this in “Bad Science” where he postulates that science gets bad coverage due to the media being dominated by humanities students.

Rees (the cynic) says “the distortion is even greater because some scientists (and some institutions) are far more effective than others in communicating and promoting their researches“.

In the pseudoscience world, have you ever wondered why “power” is often narrowly defined by the ability to be tested on a force platform? Answer: where does most of the research come from? Which researcher is on the board of the company that makes the force platform?

This power “research” is then disseminated as gospel (negative results are rarely published in journals, skewing the system further).

Even if we see a well designed study, Rees suggests we bear in mind what Francis Crick has to say “no theory should agree with all the data, because some of the data are sure to be wrong!”

Cancer is more serious than sport

The world is going to keep turning if sports scientists publish poor research about the best number of squats to produce better swimmers. But cancer is much more serious. As reported in the New Scientist, an investigation into 23-highly cited papers in preclinical cancer biology found that fewer than half of them could be replicated. This could explain why less than 30% of phase II and less than 50% of phase III cancer drug trials succeed.

The money, effort and lives at stake in this research is huge. Open access of information helps data sharing and replication (or not) of studies to see if they work. This is how science is supposed to work.

However, if information is not shared, then the studies that can not be replicated get cited more and more and become ‘impact’ papers. This can entrench a series of academics into defending their ‘worthy’ study even if lives are at risk.

Why we should ask difficult questions

Of course, we get what we deserve. Francis Bacon said this in “The advancement of learning” (1605).

Of course, we get what we deserve. Francis Bacon said this in “The advancement of learning” (1605).

“For as knowledges are now delivered, there is a kind of a contract of error between the deliverer and the receiver; for he that delivereth knowledge desireth to deliver it in such form as may be best believed, and not as may be best examined; and he that receiveth knowledge desireth rather present satisfaction than expectant inquiry.”

Steve Myrland says that we believe our own fallibility more than the person presenting to us and that “those parts of presentations that are most confusing to us tend to be the parts we question least.”

This then allows the “expert” to carry on building up an awe-inspiring reputation that remains unchallenged.

Pseudoscience and the LTAD Model

I see this a lot in pseudoscience journals from the UKSCA and NSCA: academics who have less coaching experience than our local primary school teachers are given platforms to promote their unfounded theories.

Models are not scientific evidence nor are they laws. Yet, some researchers looking at physical interventions in children and youth populations cite an LTAD model as ‘evidence’ for the basis of their exercise programming! There is no proof that the LTAD model works: no one has taken a group of children through 15 years of that programme and seen the results. It hasn’t been around for 15 years for a start! Second, every child, every school, every town and every sports club are so different that there can not be a ‘Model’ for all.

I should know: I have been coaching this stuff for 20 years and set up an Athletic Development Club to help local children. Things change so much week to week with my own 2 children, let alone term to term and year to year, that planning for 15-year progression is nonsense.

Referencing that model shows a lack of understanding. Unfortunately, once it’s published and then cited, it keeps getting cited by more and more articles until it gains ‘impact’.

I once spent an afternoon trawling through the 150 references in pseudoscience article about sprint starts in swimming. Many of them were generic points about ‘power’ or ‘sprinting’ on dry land. The few that referenced swimming starts were vague and one of them contradicted the recommendations of the author!

What is a coach to do?

‘We are drowning in information while striving for wisdom.” E. O. Wilson.

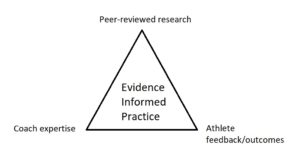

Trusting your eye or instinct is a solution fraught with difficulty: we are all prone to bias in many different forms. We can neither dismiss or accept the body of published work as ‘scientific evidence.’ As seen in the cancer studies, there are some that can be replicated and some that can’t.

I try to be open-minded when reading ‘research’ and I don’t take just the abstract and use that to change anything I do with coaching. I do reflect and review upon the coaching that I do after every session. I also check with my specialist or more experienced peers about new ideas or concepts and get their take.

Finally, I look at my situation and see if the new concept is going to help the athletes I coach get better or to make things simpler for them. If it isn’t, then I don’t use it. If it is, we trial it, observe it and see what results we get.

That is the scientific process.

Thanks to Dr Rob Frost for lending me the book.

Further reading:

- Force, power or acceleration (or how to develop power away from a force platform)

- Improper application and interpretation of statistics in sports “science”

- Sports Science for Sports Coaches

- Antifragile by Naseem Taleb

- Bad Science by Ben Goldacre

Answer: 0.6! (cynically, Rees wondered whether this included the referee).

Client Testimonials

South WestFencing Hub

South WestFencing Hub

Working with James has been a pleasure and education for all of the fencers and coaches, from beginner fencers and trainee fencers, up to international fencers and coaches with decades of experience. We really appreciate James' desire to challenge assumptions but simultaneously his ability to listen to both fencers and coaches on technical and tactical points. He manages to keep his sessions fresh and innovative without losing sight of our central goals. His sessions are challenging and fun and his attention detail is a tribute to his professionalism. Thank you.

More