Teaching Games in Primary School

Last week, a Primary School teacher told me of their experience teaching tag rugby to year 3s (7-8-year-olds),

‘We practised passing down the line a lot but, when it came to the game, they didn’t know what to do.’

Compare that to the advice given by the Department of Education and Science:

‘At about nine years of age, they may be ready to play many simple games, with three or four a side, with the object of scoring points and goals.’ (1972).

Have children developed a greater sense of gameplay in the last 50 years? Can they be put into competitive matches of 7+ a side because they are more skilful, athletic and tactically aware than the children of the 1970s? Is physical education being taught that much better at Primary School?

In my experience, no. Children love playing games but they still need the time to develop (you can see how these year-3/4 children are learning the basics but need help with movement).

Again from the DES,

‘Children at a young age play alongside each other rather than with each other.’

Trying to teach pupils sport-specific skills or rules without having the foundations of games sense and skills in place often leads to frustration among pupils and teachers alike. Many sports clubs teach only their sport and ignore underlying movement patterns (physical literacy for want of a better phrase).

Example 1: The overhead tennis serve.

This is a highly complicated skill requiring the use of both hands and an implement, before even

thinking about accuracy. Teaching this to year-one pupils is likely to result in failure for many.

Before attempting this skill, the pupils should be able to do two things:

1. Throw overhand properly (contralateral leg and arm, shoulder and chest rotation, elbow and

wrist lag behind hip rotation).

2. Throw and catch to themselves using the non-dominant hand (for the toss-up).

By working on these two throws in the early years, amongst other skills, when it comes to time to try this complex skill, they have a chance of success. The alternative is to put the racquet and ball in their hands and let them try and work it out. This may lead to success for some who possess the underlying skill or get lucky, but many will get frustrated and stop. Especially if they only have a few attempts each due to time/ equipment shortages.

An example of doing some general ball basics can be seen in this video.

Primary school p.e. is the perfect place to teach this physical literacy and that enables ALL children to learn how to move. This builds their confidence so that they can play sports if they choose or have the opportunity to do so.

What has happened to physical education teaching in the last 50 years?

Unfortunately, the dismantling of the teacher training syllabus that now leaves them with 4 hours of Physical Education training, has created a wasteland of well-meaning teachers who lack confidence and knowledge. This has opened the door for outsourcing to sports coaches who try to teach their sport to children at too early an age.

National Governing Bodies (NGBs) are desperate to ‘increase participation,’ and have the resources to offer beleaguered Head Teachers looking for a solution to a problem they do not understand.

Children queue up to learn rules and terminology rather than move, learn, and have fun. The teachers are given colourful ‘flash cards’ and ‘resources’ that they can read from.

But, if they don’t understand the premise behind physical education, then the chances of children learning are haphazard: a few will get better, some will get better DESPITE the lesson, a few will misbehave and most will come away a bit tired (optimistically) and have learned nothing.

Each NGB is fighting for a piece of the pie so they try and recruit early to get ahead of the other sports. The poor children (and parents) are then caught in the race to specialise early. This is problematic for two main reasons:

- There is no evidence that specialising early leads to success at an adult age.

- By focussing on sports rules, only the early developers and those with exposure elsewhere ‘succeed.’ Everyone else gets disheartened, bored or finds something else to do.

How sad is it to hear children say, ‘I’m no good at sport,’ at 8 years old?

They shouldn’t be good/ bad, they should enjoy playing games. And that’s where Educational Games come into play.

Helping Children Develop Their Games Sense

Premise: skill development and decision-making for games players are interlinked and should be

taught together.

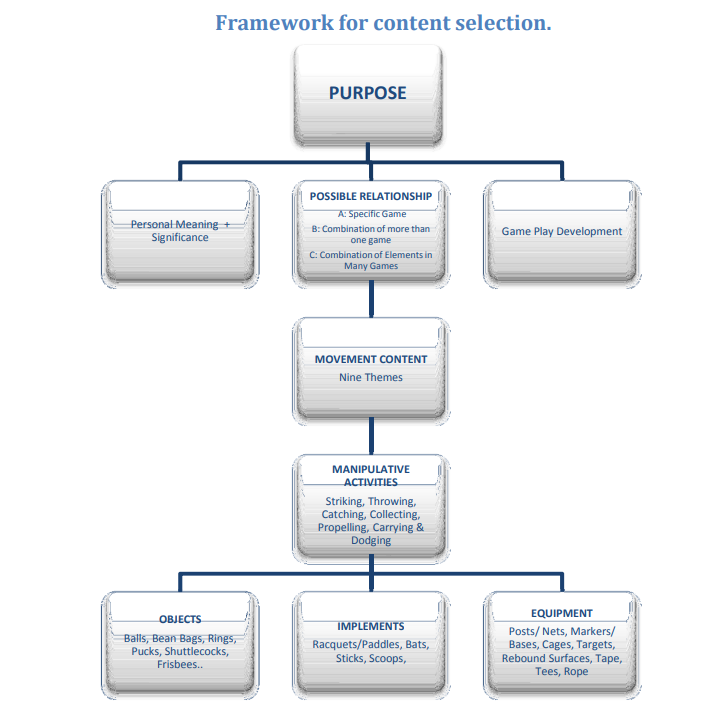

By using a framework to operate from, teachers can plan lessons easily and allow pupils to be more involved, and creative and learn at their own pace.

Playing specific games requires the learning of often complicated rules that require the child to

memorise as well as trying to control their own body, control an implement and deal with opposing team members.

Developing the children through Educational Games means that they are then able to learn sport-specific skills and apply the rules more easily if they choose to participate.

Outline:

Below is the framework for teachers to use to plan their lessons. Each workshop I run draws on different aspects of this framework to show how it can be used in daily teaching.

I teach different lessons depending on the age/ stage of the children and explain which aspect I aim to develop in each lesson.

The aim is for the teachers to see the overall strategy, see how it is implemented in a single lesson and understand how to develop the children from there.

Movement underpins every sport

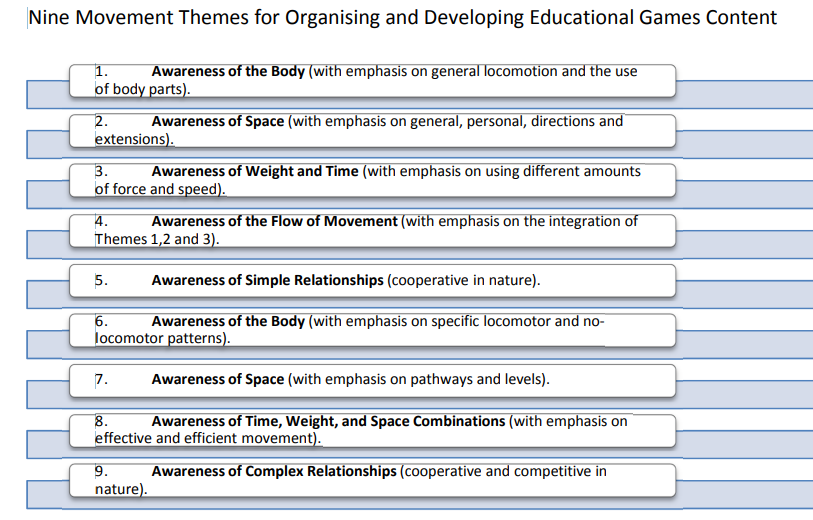

Every lesson has some movement aspect in it: the children can not be too physically literate. There are nine themes that I use (based on Laban’s work) and they can be integrated into every lesson.

Instead of a series of drills that have to be memorised, the children get to develop their own patterns through some guided discovery, exploration and solving of tasks. This requires less demonstration/correction from the Primary School teachers (much to their relief).

One of the reasons that children struggle with physical literacy and games sense is that the teachers lack the confidence to teach them. Every teacher can read and write, not every teacher can throw, catch, skip, run, jump and strike a ball.

It is very rewarding to coach children and see them develop. It is almost as rewarding coaching teachers and seeing them grow in confidence as they realise there is more to physical education than rules, queues and shooing chickens.