IFAC reflections Part 1

Leave a CommentA review of the middle day of the IFAC conference in Loughborough.

I spent the first Saturday of 2019 at the EAAC event held at Loughborough University. Finding good conferences in the UK is hard, so I wanted to make the most of this opportunity.

I shall give an overview of what I learnt, plus some detail on the specific exercise progressions in the gym.

Whilst the term athletics may turn readers off, the principles and movement inherent in these workshops apply to many different sports. Frank Dick is the organiser. The ex head coach of UK Athletics in the early 1990s is the author of three excellent books and is the main reason I wanted to attend.

I have met Frank 4 times previously. The first at “Bodylife” a Health Club conference in the late 1990s where he was the key note speaker. His talk influenced me to later set out on my own path rather than continue down the management track.

I then attended a 1 day leadership and coaching workshop with him in 2000, where he took us through a great day of practical coaching and thinking exercises. I was there with a small team of my staff who were great people too.

I next saw Frank accompanying his daughter trying to rack up tennis points at the David Lloyd Club I was managing in Heston. We talked then about the tennis system and how much travelling was required in order to gain these points.

Forward onto 2012 and the buzz about the London Olympics. I attended the Global Coaching House in Piccadilly which he organised and I saw a variety of great coaches speak.

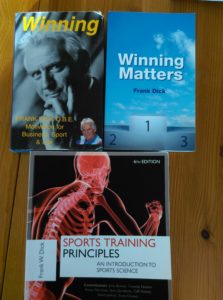

The three books he has written are:

• Sports Training Principles: currently in its 5th edition, a sport science text that has expanded and become more detailed over the years. I first read this in 1993 and recommend it highly.

• Winning: A great short book about motivation in which Frank talks about “Mountain people and valley people”

• Winning Matters: A guide to leadership and running a successful club or organisation. Again, very useful.

So, whilst I haven’t ever been coached by Frank, I have been influenced by him and he has definitely given me inspiration through speech and the written word.

Fit for purpose: functional physicality

Martin Bingisser gave the first presentation on what constitutes physical preparation for sports. Martin has represented Switzerland at the hammer throw and now coaches throwers. He runs HMMR media and I was invited onto his podcast last October. I met Martin at GAIN 3 years ago and have enjoyed getting to know him.

“Understanding why is the new functional training”.

New coaches are keen on the “What” with some “How”. Which new exercise can they copy from a famous athlete on Instagram? Martin was keen to stress the “Why” we do exercises and that as coaches evolve, they ask this more and more.

(These phrases come from Simon Sinek’s book “Start with why?” and are common to GAIN coaches).

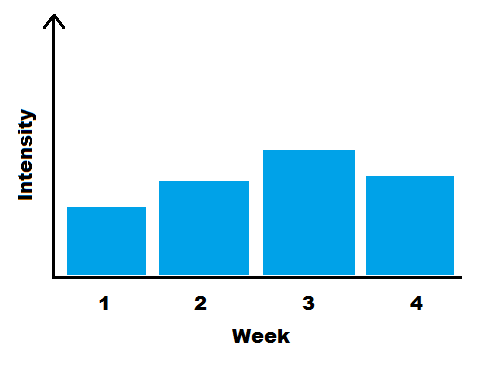

Martin split the concepts of physical preparation into 3 stages:

• General

• Related

• Specific

(attendees of our coaching courses will recognise this is also how we structure how warm up design).

General: To prepare athletes to train.

Jesse Owens jumped 8:17 metres in 1936. He never did a back squat (or a mid-thigh pull). How was he able to compete in 4 different events and win Olympic Gold Medals without going in a weights room?

Growing up in the segregated south, his active youth may have been the “General” preparation that was necessary.

Martin then showed videos of the La Sierra High School physical education programme espoused by John F Kennedy in the 1960s.

The video shows what can be down outside if young people are given the opportunity (It was one of the influencers in choosing the equipment with our Parish Council for our village’s main park).

Why Squat?

Why is the back squat so prevalent and now seen as a “need to do” exercise? How about:

• Goblet squat

• Partner squat

• Single leg squat

• Half squats

• Step ups

as examples of developing leg strength?

Martin then gave several examples of different athletes doing different leg exercises, each of whom had a rationale for their situation and purpose.

This is different from saying “You MUST do back squats”, especially with beginner athletes and beginners in the weights room.

(Martin was preaching to a choir boy with me, and our club members will recognise the patterns and themes that we follow. This is covered regularly at GAIN and in different variants).

Related: Prepare athletes for the sport

Martin showed a video of John Pryor doing some “Robust Running” drills with the Japanese National Rugby.

The difference between “cool looking exercises on Instagram” and a purposeful approach to coaching, with structures and progressions was the main point here.

Key points were:

• Develop skill execution in parallel with physical prep.

• Constraints- led approach so the athletes have to solve problems to create the correct sprinting pattern.

• A simple approach to a complex environment means that one piece of the puzzle can be solved at a time.

Specific Training for the sport

Time needs to be spent doing this. Do coaches look for ways to structure their training accordingly? Do they know the needs and demands of their sport?

Martin showed a video of a shot putter training with some “cool looking exercises”, but then explained why they were “sport specific”.

They consisted of four elements which transfer to the sporting environment:

- Technical/ co-ordination– develop balance and rhythm through an altered environment.

- Mental– create a challenge to help focus.

- Strength– specific strength overload.

- Emotional- competitive challenge.

When designing programmes to improve physical preparation for the sport, coaches need to know the basics required in that sport. Is there a relevant measurement for exercises that can be found- or, like Jesse Owens, do we just need to be fitter?

The final point from Martin was that the best coaches need:

ADAPTABILITY + VERSATILITY