Main Menu

Latest Blog Entry

User login

History of Educational Gymnastics in British schools

Educational Gymnastics in Britain

A popular conception of gymnastics today is of young girls in sparkly leotards with hair kept up in tightly bound buns. This is a relatively new concept, with gymnastics originally being an all-male outdoor pursuit.

Gymnastics has originated from several different sources, but all had the underlying principle of healthy movement. The last 30 -40 years has seen a swing to competitive gymnastics which has influenced coaching courses and also teacher training. This so-called “traditional” gymnastics in clubs results in a massive dropout by children in their early teens.

With phrases like “disengagement” and “pupil-centred” learning becoming prevalent, teachers may be in the frame of mind to look a little bit deeper into our rich and varied past for ideas that were successful with previous generations.

This article shall look at the origins of educational gymnastics and also offer solutions for teachers and coaches who wish to improve the overall movement of their pupils and players.

Gymnastics and the defence of the Nation

The many wars and conflicts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries meant that all European Nations were worried about the health and fitness of their military recruits. The history of gymnastics is intertwined with the concerns of each country about possible invasions by the enemy.

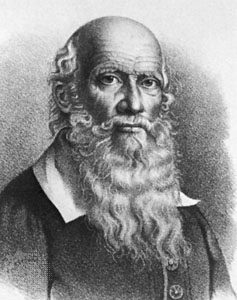

Frederich Ludwig Jahn was probably the first gymnastics coach. He was a teacher in Germany and he trained boys in the woods outside Berlin to help prepare them for military service against Napoleon (1). The boys performed all types of stunts using tree limbs and natural features. When they moved inside in the winter, “Father” Jahn built apparatus to help reproduce this work.

These ideas spread to other areas and competitions between the groups developed. The groups were known as “Turnvereine” and the participants as “Turners”. In the 1820s many Germans emigrated to North America and continued their practice especially in the big cities. This led to the formation of the “American Turnerbund” which had a big influence in introducing physical education to public schools.

In France in the early 1900s, a similar approach was developed by Georges Hebert. Hebert had served with the French Navy and was involved in the relief of Martinique after a volcanic eruption. This disaster shaped his thoughts on the need for physical fitness, courage and altruism.

His travels led him to observe people on different continents and he reflected:

“Their bodies were splendid, flexible, nimble, skilful, enduring, resistant and yet they had no other tutor in gymnastics but their lives in nature.” Georges Hebert (2).

He started to develop his “Natural Method” based on these ideals and also the work of Frederick Jahn amongst others. He systemised the exercises and practised them. Hebert was injured in World War I and was then asked to form a school of physical education for the French Military.

“The final goal of physical education is to make strong beings. In the purely physical sense, the Natural Method promotes the qualities of organic resistance, muscularity and speed, towards being able to walk, run, jump, move on all fours, to climb, to keep balance, to throw, lift, defend yourself and to swim.” Georges Hebert (2).

Hebert helped develop obstacle courses that allowed recruits to perform a series of various exercises in sequence. This then became standard practice for nearly every military unit in the world before World War II (Parcours du combattant = Assault Course), more on this later.

Swedish Gymnastics and Swedish PT

At about the same time Father Jahn was developing his system, Pehr Henrik Ling was creating a series of formalised exercises in Sweden (3). He did this after studying to be a Doctor and was in interested in the health-promoting benefits of regular exercise.

In 1813 Ling was given government backing and founded “The Royal Gymnastics Central Institute” in Stockholm. Amongst other things, Ling is credited with inventing Calisthenics (derived from the Greek words Kalos and Sthenos: Beauty and Strength) and several pieces of equipment including wall bars, beams and the vaulting box.

Ling’s systematic use of a series of exercises proved popular in the early twentieth century and easy to export.

(P.G. Wodehouse mentioned them several times in his novels:

Aunt Dahilia to Bertie Wooster “Well, I won’t keep you, as, no doubt, you want to do your Swedish exercises.” (4).)

In 1909 the British Board of Education issued a “Syllabus of Physical Training” which was based on the Swedish PT system (5). This involved an enormous amount of exercises and routines which were annotated like this:

“Exercise 36 (St-Kn.Fl.Bd.) Jump to St.-Asd.-Hl. Ra. Posn. With Am. Bend. U. or swing. m.

(With heel raising, knees full-bend!) Jumping astride on the toes with arm bending upward (arm swinging midway), by numbers one!- two! And later: Five times- begin! Spring from one position to the other, bending the arms upward or swinging them midway on the upward jump and bringing the hands to hips on the downward jump. The number of jumps may be gradually increased.”

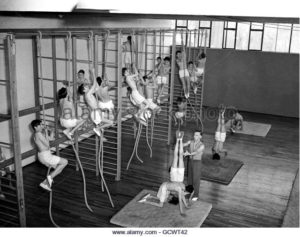

This syllabus did include apparatus work with the wall bars, beams (heaving) and vaulting boxes as well as rope climbing.

There was little or no individual development or coaching, it was designed for mass instruction and synchronised movements. The Board of Education were still using it in the years immediately after World War II.

Here is an example of how it was used outside of schools too:

Gymnastics in Britain around the Wars

After World War 1 a new philosophy of physical education was developed: informal activities and mild recreational activities became the norm. Gymnastics, tumbling, callisthenics and marching tactics were reduced further before World War II in some areas.

As the threat of war loomed once again the 1930s, the government once again took interest in the health of the young men. This video shows some of the formal work being done in a standard physical education class. Note the precision of movement, agility and also body mass of the children involved.

In the 1950s and 1960s, gymnastics on apparatus enjoyed a resurgence as many ex-servicemen went into teaching and taught activities they had done in the military (6).

The origins of Parkour

In 1946 a 7-year-old French orphan called Raymond Belle snuck out of his orphanage in French Indo-China (now Vietnam) to train in secret to avoid becoming “a victim” of the very real conflict that surrounded him. He set up a series of exercises and routines in the jungle that he practised diligently for the next 9 years. He moved to France at the age of 19 and served in the French military (7).

His son David Belle was inspired by his father’s accomplished physical capabilities and his philosophy on life. David did gymnastics and athletics growing up but found them “too scholastic” for his taste.

Rather than do sport to compete, he wanted to seek out challenges for their own sake and find new ways to move:

“And that’s exactly what Parkour is all about: move from one obstacle to the other and make it more difficult on purpose so that in real life, everything seems easier.”

You can see the inspiration for much Parkour training, school gymnasiums and trapeziums in this short video.

As David grew up in a city, his obstacles were walls, ledges and rooftops, rather than the jungle or “Parcours du combattant”. It was just the Parcours.

“The aim of the game was to adapt to just about any surrounding, always keeping in mind that should anything happen, what do you do?”

I see many young teachers looking for Parkour ideas for their pupils and expecting a series of moves. But, the original concept by Raymond and then David Belle is to seek challenges and solutions themselves rather than doing stunts just to look good.

(When I coach gymnastics, I always include some obstacles or apparatus for them to work on and over. Schools do have this equipment; it just needs to be put out). These 2 children found solutions to the obstacles I laid out:

Rudolf Laban and female physical educators

So far, so martial. A completely different strand of gymnastics evolved from the pioneering work of Rudolf Laban. The Hungarian born Laban was resident in the UK from 1938 until his death in 1958(8)

His background and speciality was movement through dance. He spent years observing and practicing teaching pupils’ movement. Laban’s work has been summarised in 5 statements:

- That all human movement has two purposes, functional and expressive.

- That dancing is a symbolic action.

- That all movement of a part or parts of the body is composed of discernible factors that are common to men everywhere. These factors are contained in two overall terms: effort and shape.

- That there are inherent movement patterns of effort and shape which are indicative of harmonious movement.

- A system of notation that makes it possible to record accurately all movement of the human body.

The emphasis is on helping the participant discover new or more efficient or expressive ways to move. This contrasts with a “Top Down” approach of having an end skill such as a forward roll and trying to get every pupil to do that by the end of the term to “demonstrate learning”.

“Physical Education students abhor the fact that they are given too much chapter and verse; taught a recognisable end-product, and not allowed more individual interpretations.” (8).

Laban’s detailed observations and the systematic annotation were taken up by female educators such as Ruth Morison (10) and Mauldon & Layson (11) who wrote very accessible books that expanded the ideas and applied them more to the functional side of gymnastics, rather than the expressive side of dance.

When I first started researching Educational Gymnastics, I couldn’t work out why it was only female pioneers. Then I realised the huge impact World War II had on this generation and the men were away for 6 years of Laban’s work. Plus, the schools of Laban movement were dance-based and so there were mainly females being exposed to his work and the initial talk was of “movement” training rather than “gymnastics”.

Laban’s movement framework could be summarised as follows:

Expansion of these ideas was piecemeal with Lancashire and Yorkshire being the “early adopters”. Several more Educational Authorities soon realised that this framework and a child-centred approach meant that teaching gymnastics was a lot easier for Primary school teachers without a specialist background (12, 13).

“The gymnastic lesson today is centred on the child rather than the exercise. The teacher tries to create a learning situation which will stimulate the child to think.” (13).

Here is an example of my coaching “Rocking and rolling” (body aspect with shapes and actions).

Whilst there was still a distinction between boys and girls gymnastics in the 1960s and early 1970s, male educators who became exposed to Laban’s methodology realised its use too (14). The combination of learning how the body moves, then applying that to using apparatus in the gym meant for a potentially rich, inventive and fun environment for the children.

“An inventive child with a certain degree of skill will produce varied work instead of movement clichés or actions habitually strung together.” (11).

However, whilst the knowledge of specific skills was unnecessary, teachers had to have empathy, sound movement knowledge and great observational skills for this system to work. So whilst it may be easier to plan structure for Educational Gymnastics than rote learning, it also requires a teacher who can think on their feet.

There was some resistance amongst male educators who were used to a “command-response” approach utilised by the Swedish PT system and/ or their military service. (Younger readers might be questioning my continued use of gender: it is relevant to the times, some context of how “new-fangled” ideas might have difficult spreading can be gained by watching Brian Glover’s portrayal of a games teacher in Kes (1969)

Note that this “creating of learning environment” and “child-centred” approach was being written about and conducted with success from the early 1960s onwards. This predates the work on “constraints led coaching” by over 2 decades (15).

School gymnastics today

It is for better-informed people than me to try and explain what has happened to physical education in this country since the early 1970s. Part of the problem is that even if the National strategy is well informed (take this from 1972 for example):

“In his inheritance, in response to his environment, in his biological need for activity and in his absorption in the potential of his physical frame, a child has within him a powerful drive to indulge his capacity for movement. It is the role of physical education to reveal and extend this capacity, and through it to lead the child towards his full potential.” (16).

Local Authorities Vary

For example in East Sussex, Teachers were given guidance by University lecturer and a Senior BAGA coach which dismisses the Laban based work as “an activity shrouded in a “movement mystique.” (17).

Their book simplifies “gymnastics” to 7 specific skills and recommends following the BAGA award scheme “since it has clearly defined objectives”. I would suggest that this is the antithesis of “Educational Gymnastics” and is more like “training” which is commonly seen in gymnastics clubs.

“Training is a reductionist goal: its aim is to refine an existing action, whereas learning is an expansive goal; its aim is to increase the number of potential actions.” (18).

That is just one example, but each county will have its own adviser and system of teacher education.

One underlying problem now is that teachers coming into Primary Schools receive as little as 4 hours of Physical Education tutoring. Today’s kids are being taught by teachers who have never been exposed to physical education programmes themselves.

(On a recent course I tutored, one 23-year-old sports science graduate didn’t know that the sports hall benches could be secured safely against wall bars with the levers underneath!)

Many “P.E. specialists” have studied Sports Science courses at University, rather than Physical Education. They are more comfortable measuring physical fitness than teaching movement.

Helping the teachers teach and the children explore

I started learning about gymnastics in order to help my own children. Coming into it with an open mind, without a competitive gymnastics bias, or a local authority slant, I just focussed on giving the children the best opportunity to learn in a limited amount of time.

For me, the Educational Gymnastics work tied well into my own coaching philosophy developed through working with accomplished sportspeople at Regional and International level. I could see the end goal, but reverse engineering from that and doing “micro versions” of “elite” training was nonsensical.

Instead, building the child’s ability from the ground up in an environment that is both challenging and rewarding is both our club’s aim, and that of the village school where I teach. Laban’s work looks at developing movement from within whilst Parkour looks at overcoming obstacles from without. Combining the two together has been a learning process for me and our club gymnasts.

No child has yet to come to me and ask for a certificate, badge or to enter a competition. Their motivation comes from within.

The coach and teacher “Educational Gymnastics” course I developed has helped introduce teachers to the infinite possibilities that children can explore. By giving them a framework and practical ideas, they gain confidence and observational skills that they can take back to their own unique classrooms.

There is hope for us all yet, we have a rich tradition in this country, I hope this article as given you some ideas for helping your children learn and explore movement.

Teacher Training: Educational Gymnastics CPD Day

References

- A Manual for Tumbling and Apparatus Stunts: Otto E. Ryser (1968, 5th edition).

- Le Sport contre l’Éducation physique: Georges Hebert (1946, 4th edition).

- A Biographical Sketch of the Swedish Poet and Gymnasiarch, Peter Henry Ling: Georgii, Augustus (1854).

- Right Ho Jeeves: PG. Wodehouse (1934).

- Reference Book of Gymnastic Training for Boys: Board of Education (1927, reprinted 1947).

- Activities on P.E. Apparatus: J. Edmundson & J. Garstan. (1962).

- Parkour: David Belle & Sabine Gros La Faige (2009).

- The Influences of Rudolf Laban: John Foster (1977).

- The Mastery of Movement: Rudolf Laban, Revised by Lisa Ullmann (1971).

- A Movement Approach to Educational Gymnastics: Ruth Morison (1969, reprinted 1971).

- Teaching Gymnastics: E. Mauldon & J. Layson (1965).

- Educational Gymnastics: Inner London Education Authority (1962, reprinted 1971).

- Education In Movement (School Gymnastics): W. McD Cameron & Peggy Pleasance (1963, revised 1965).

- Gymnastics: Don Buckland (1969, reprinted 1976).

- Constraints on the development of co-ordination: Newell, K.M. In Motor Development in Children: aspects of co-ordination and control (1986).

- Movement: Physical Education in the Primary Years: Department of Education and Science (1972).

- Gymnastics 7-11: A lesson –by-lesson approach: M.E. Carroll & D.R. Garner (1984).

- A constraints–led, systems based autodidactic model for soccer or how guided-discovery works: Paul . In 21st Century Guide to Individual Skill Development Brian McCormick (2015).

Client Testimonials

Josh Steels: wheelchair tennis

Josh Steels: wheelchair tennis

I started working with James 3 years ago via the TASS programme. When James first met me, physically I was nowhere the best I could be. Since working with James I have seen vast improvements in my fitness and strength which has been put into great use on court. Each session is worked around making sure I am able to get the best quality training as well as catering for my chronic pain and fatigue levels. On top of this James has always been happy to meet at facilities that are best for myself meaning I could fit training sessions in on route to tournaments or camps.

More

Comments

What a great article! I trained to teach educational gymnastics in the early 1980s and have been teaching it ever since. I spent 17 years in secondary schools and am in my 19th year in primary PE. I am soon to retire and I want to set up a company that delivers educational gymnastics sessions in primary schools and trains teachers to do the same. Although I am capable of teaching specific skills, my approach is mostly creative using the Principles of Movement. I also teach dance (aka Laban) using the same methodologies.

My biggest concern is that primary schools do not used their gymnastic apparatus fully and a key purpose of my planned work is to support schools to “dust off their gym apparatus” and use it!

I would love to connect with your company. I operate in Yorkshire and Lancashire. Where are you based?

Diane

We are based in Devon

who wrote this article ?

James Marshall: I write all of them unless it is a guest post and then the author is introduced or credited.