Main Menu

Latest Blog Entry

User login

How training the Central Nervous System helps you become a better athlete

The Sporting Brain: Understanding how the mind helps us play sport

Top cricket batsmen have been reported to hit balls within a time window of 2 to 3 milliseconds, that’s the same speed as a house fly’s wing flap! The Central Nervous System is an essential part of this skill.

Have you ever wondered how they do this? More simply if someone throws you a ball, you catch it. But have you ever wondered how seeing that ball results in our body moving to catch it? How does what we see (visual stimuli) result in movement?

Our brain process all the information we receive via sounds, sight and touch, but how does this result in movement? All of these systems, including the visual system, are part of the central nervous system.

The Central Nervous System (CNS)

The CNS is the brain’s first branch of the nervous system and consists of two parts:

- The brain

- The spinal cord

The CNS is connected to the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The PNS is then connected to

- Sensory organs (e.g. eyes and ears)

- Muscles

- Blood vessels

- Glands

- Other organs

When we see something (stimulus), our eyes (receptor organ) collect information which is then relayed, to the CNS. The CNS then interprets this information and sends it back to effector organs (i.e. muscles) which then carry out the body’s response to the original stimuli.

For example a cricket fielder sees a high ball coming towards them and their body reacts to catch it.

Playing sport affects how the CNS controls muscle recruitment and action.

Research that tested vertical jump performance in swimmers, jumpers and football players found that, not surprisingly, jumpers had the most powerful jumps (Eloranta, V. 2003).

However using information gained directly from the muscles, they attributed this to the CNS influencing the firing and recruitment patterns of the muscle. Jumpers had optimum firing and recruitment for maximal jumps, whereas swimmers muscle firing and recruitment was more suited to kicking and therefore resulted in a poorer vertical jump.

Eloranta (2003) concluded that ‘prolonged training in a specific sport will cause the central nervous system to program muscle coordination according to the demands of that sport’.

They also found that this learned reflex could interfere in the performance of another task.

A New Theory!

A recently proposed theory for processing ultra fast events suggests after information is relayed to the CNS there are in fact two streams of processing what we see.

1) The ventral stream, providing information for perception

Involved in object recognition

2) The dorsal stream, resulting in action.

- Involved in spatial awareness

- Involved in guidance of objects

These two systems work independently from each other and at different speeds!

Visual stimuli results in electrical signals being sent to LGN (a sensory relay nucleus in the brain) where they are sorted and sent back to the visual cortex.

Any signals that result in gross motor movement go through the dorsal stream with more sophisticated signals heading down ventral stream.

The ventral system is tailored for situations where the movement times are longer and there is adequate time for cognitive processing to occur. The dorsal system is specialised for tasks performed when movement times are shorted and therefore affected by time constraints.

More simply the ventral stream is used when you have time to think about your actions (assessing the situation when deciding to go for a conversion or a try during a penalty in rugby) and the dorsal stream is more automatic (catching a falling plate or returning a ping pong ball).

How They Were Discovered

These two pathways were discovered by Goodale et al., (1991) when a woman who suffered carbon monoxide poisoning was tested for visual defects. She was unable to identify common objects yet seemed to still be able to use her motor system to control her hand movements.

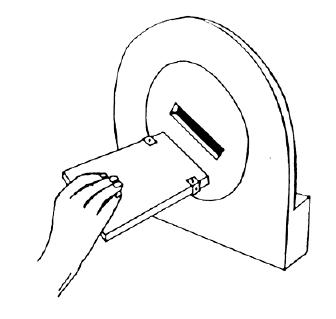

A round disc (picture below) with a slot in it was placed 45cm away from her and she was asked to draw the angle of the slot. She was then asked to post a piece of card through the slot.

The results showed that when asked to draw the angle of the slot she failed (ventral stream), however when asked to post the card through the slot (dorsal stream) she could orientate the card at the right angle every time.

This showed damage to one system without affecting the other system, highlighting the evidence of two separate systems.

Perception vs. Action

Although there seems to be striking evidence that there are two separate systems, there is still much debate over how segregated these two streams really are.

Research has suggested they work closely together and are heavily interconnected (Farivar, 2009).

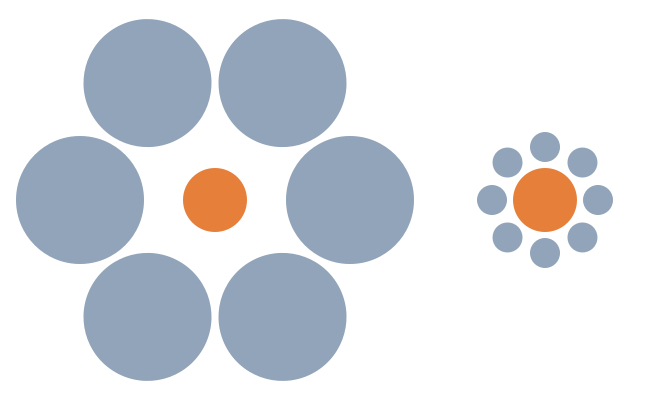

Much support comes from visual illusions such as the Ebbinghaus illusion and Müller-Lyer illusion (Pictured below). These illusions may distort judgments of a perceptual nature (ventral stream), but when the subject responds with an action (dorsal stream), such as grasping or pointing, studies have found no distortion occurs.

Figure 1: Ebbinghauillusion

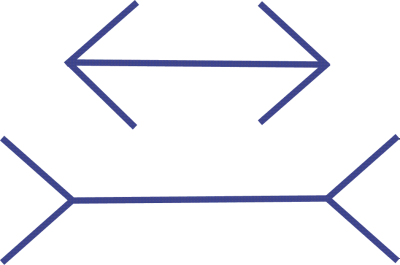

Figure 2: Müller-Lyer illusion

When asked to draw the diameter of the circles or the length of the line participants drew the right hand circle diameter and the bottom line longer. However when asked to show the diameter or length using their finger and thumb there was little difference between the two images.

Illusions like the ones above seem to affect the perceptual (ventral) system but not the action (dorsal) system. Participants perceived the circle and line to be distorted but when using an action to illustrate it they were not fooled!

It is important to note however, some contradictory research finding that these illusions can fool both the ventral and dorsal systems equally (Franz et al., 2000; Franz, Scharnowski, Gegenfurtner, 2005; Franze, Hesse & Kollath, 2008).

How does the Central Nervous System relate to sport?

We know that the dorsal system is used to visually guide movement execution. For instance, it controls the execution of a tennis stroke such that the ball will be hit at the right place, at the right time, with the right amount of force.

The ventral system is involved in the perception of objects, events and places. As the ventral system obtains knowledge about what the environment offers for action, it can also contribute to action.

It may, for instance, gather information whether a down-the-line or cross-court shot would be the most appropriate action (van der Kamp et al., 2008).

It is important to be able to enhance both of these systems, not just one.

‘In most sports it is important to react quickly and decisively whilst also being able to evaluate what is going on and take in your surroundings’ (Morris, S, 2009). It is also important that these two systems don’t interfere with each other.

When these two streams are working together in harmony, they make it possible for you to rapidly respond using the action process whilst simultaneously taking in the bigger picture with the perceptual process.

The perceptual stream is conscious, and allows you to strategise and plan ahead while the action stream takes care of itself.

Hockey skill under pressure

For example a footballer or hockey player, whose two systems are enhanced and working together, can plan where there next pass or shot is going whilst receiving and dribbling the ball.

Training these Systems

You need to challenge both processes in a competition specific environment to develop and enhance them. Working both streams during training will help you to improve.

Things as simple as listening to music or having a conversation about something irrelevant to training whilst practising specific skills, will work both systems.

The aim is to be able to perform specific skills (i.e. throwing, catching, punching, and kicking) in a competition environment, using the dorsal (action) system, whilst using your ventral system to process other information.

Therefore during a game or a competition you can perform these skills whilst assessing the environment and opposition.

Conclusion

- The CNS is the control centre for all information we need to process resulting in movement.

- It is now believed that there are two systems that process visual information, the action (dorsal) and perception (ventral) systems.

- It is important to train both of these systems in order to enhance them and improve sporting performance.

A skilled athlete who can use these two systems effectively will be hard to beat!

A skilled athlete who can use these two systems effectively will be hard to beat!

Skill development and rehearsal form an Integral part of our Training Programmes

Information for Sports Coaches

The skill development is one reason why we have restructured our strength and conditioning coaches and named them Athletic Development Coach

Too much “S&C” work is gym based and lacks skill. We are only interested in what works on the pitch and court.

References

Eloranta, V. (2003). Influence of sports background on leg muscle co-ordination in vertical jumps. Electromyography Clinical Neurophysiology. 43(3):141-56

Farivar R. (2009). Dorsal-ventral integration in object recognition.. Brain Res Rev. 61 (2): 144-53

Franz, V. H., Gegenfurtner, K. R., Bülthoff, H. H., & Fahle, M. (2000). Grasping visual illusions: no evidence for a dissociation between perception and action.. Psychol Sci. 11 (1): 20–5.

Franz, V. H., Hesse, C., & Kolath, S. (2008). Visual illusions, delayed grasping, and memory: No shift from dorsal to ventral control. Neuropsychologia, 47:6, 1518-1531.

Franz, V. H., Scharnowski, F. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. (2005). Illusion effects on grasping are temporally constant not dynamic.. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 31 (6): 1359–78.

Goodale, M. A.,Milner, D., Jakobson, L. S., & Carey, D. P. (1991). A neurological dissociation between perceiving objects and grasping them. Nature. Vol 349.

Client Testimonials

Judith Hamer – GB Wheelchair Basketball, Paralympian

Judith Hamer – GB Wheelchair Basketball, Paralympian

I have worked with James for three years now. James's attitude to training has changed my approach to my training session and sport making me more focussed and organised to get as much as I can out of each session. The improvements I have made with my fitness, core and my psychological approach to training have been largely down to my sessions with James

More

Comments

[…] activates the Central Nervous System […]

[…] The Central Nervous System has been affected, so this must be trained too: “It is not a race to get them back, it is a process to get them better” Gambetta. […]

[…] Muller Lyer illusion is an example of System1/ System 2 conflicts. Our initial impression is that the lines are […]

So interesting. Are you able to suggest specific practical drills re: listening to music or talking irrelevent stuff whilst doing a drill

cheers max

In coaching parlance, that type of distraction is known as “contextual interference”. You can either do it purposefully, or not. I am not a big fan of music in training, especially with kids. It can be too much of a distraction, especially if they start choosing/ arguing.

Better to have relevant cues like other players.