Main Menu

Latest Blog Entry

User login

What is Dynamic Correspondence?

Dynamic Correspondence: Is it misunderstood?

The greatest challenge for any strength & conditioning/athletic development coach is to elicit specific adaptions on the athlete in order to gain an advantage on the field of play. Specificity can arise in the form of biomechanical, metabolic, or psychological adaptations1. However, recent focus on specificity has taken on a new chapter, with the development of Siff & Verkhoshansky’s2 dynamic correspondence model.

Definition

Dynamic Correspondence: This concept emphasises that all exercises for specific sports be chosen to enhance the required sport motor qualities/movement patterns in terms of several criteria which include:

• the amplitude/direction of the movement

• the accentuated region of force production

• the dynamics of effort

• the rate and time of maximum force production

• the regime of muscular work

Furthermore, the theory proposes that the strength displayed in the execution of a given movement be referred to only in the context of that given task.

Sport movement tasks are specific and goal-directed and the enhancement in their execution should also be treated as such. Because of this, exercises should be evaluated based on the type of transfer that they may possess in relation to the degree of skill performance increase.

After this is established, exercises and/or training techniques can further be classified into categories such as general physical preparation (GPP) or special physical preparation (SPP).

Force Velocity Curve

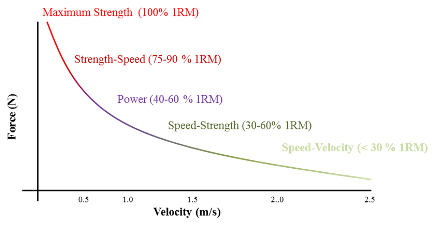

Evaluating the effectiveness of DC can only be decisive with the use of the force velocity curve alongside this argument. The force velocity curve (figure 1) shows an inverse relationship between force and velocity (e.g. the heavier the weight you lift (force), the slower you lift it (velocity); conversely, the lighter a weight, the faster you lift it).

Figure 1: The force velocity curve and its suggested training values

Therefore, different types of training occur on different parts of the force-velocity curve. As you go from high force, low velocity to low force, high velocity, you go from max strength work all the way down to speed strength work on the other side of the spectrum.

Force Velocity and Dynamic Correspondence

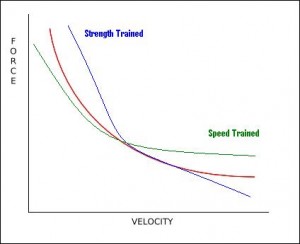

So how does this help athletes and does the curve work in unison with DC? It is agreed that a desired effect of training is to produce greater force outputs at a higher velocity compared to pre-training values 3.

Figure 2 shows what happens to the force velocity-curve after strength training (blue line) and speed training (green line).

Figure 2: The force velocity curve and its relationship with strength (blue) and speed (green) training

In advanced athletes, if you train at one end of the force velocity curve, you will improve that part of the curve, but the other will decrease. so can we train all the way along the force-velocity curve?

The problem is your body can only adapt to so much. If you train all strength qualities at the same time, you won’t adapt optimally, hence why periodisation has taken on significant popularity amongst sports coaches.

One principle of periodisation is to move from general training to more specific training 4. Strength is just general preparation whereas power and speed are more specific. So your periodisation plan should travel from left to right down the force-velocity curve .

This concept, however is not new to the strength and conditioning world; Kurz5 highlights how the strength training year needs to be divided up into 3 phases:

- General strength.

- Functional strength.

- Specific strength.

This seems to clash with DC’s suggestion on enhanced specificity.

In conjunction with this, the main bulk of research into the DC theory seems to advocate Olympic lifting, a highly specific and technical exercise, as the main component to enhance sporting capacity.

Olympic Lifting

The snatch

The use of DC alongside Olympic lifts in a programme seems to be the most popular training method when searching the current literature on the topic.

According to Stone et al.,6 the hang power clean/snatch is a dynamic lift that is multi-jointed with a need for co-ordination and fluidity within the movement, which will increase power production and sports performance in an athlete.

The argument being that this lift incorporates the triple extension with the force that is required, ensuring that the correct amplitude and direction of the force is apparent with many sporting movements, such as the engagement of the rugby scrum.

However, on closer inspection of the scrum it seems the primary direction of force is horizontal rather than vertical!

Hori and colleagues7 suggest that the rate of force development from the hang clean/snatch exercises in Olympic lifting also has a realistic transfer for rugby players. This part of the lift (2nd pull) exhibits the most force, ensuring the lower limb contracts at speed to hold a dominant position during the engage of the scrum. This would seem to tick several of the boxes in the DC checklist.

Limitations of the DC theory

From all the information above it could be suggested that the use of Olympic lifts in the athletes programme will be a useful addition to rugby forwards. However, research needs to further its examination into the effect of Olympic lifting on other sports; as the bulk of work seems to come from heavy contact sports such as Rugby Union/League and American Football.

Three notes of caution should be considered before assuming DC and Olympic lifting guarantees specific athletic training.

Firstly, one could misinterpret the conditions of dynamic correspondence to mean that an athlete must literally copy the specific sport task during the training movement.

This occurs quite often when you jump utilising a weighted vest, sprints towing a sled, or swings a bat representing a heavier load than the individual typically swings.

These types of methods have been shown to be effective at times depending on the load being utilised but they also have their limitations. For example, larger loads often greatly alter the biomechanics of the movement which, in turn, will most likely force the athlete to alter finally rehearsed movements.

Second, in an attempt to accelerate the progress of the athletes, many sports performance professionals will implement dynamic correspondence too early in the progression of an athlete’s mastery.

An attempt to have certain athletes, especially young athletes, perform exercises of specific nature before they are fully ready will only inhibit the long-term athlete development of the given individual.

The reason for this is he/she may not have attained sufficient levels of general physical qualities (such as strength or flexibility), optimized sporting skill technique, or perfected appropriate neuromuscular programs prior to performing exercise of a specific nature

Finally, once incorporation of these training exercises are employed, one must address the all-important issue of just how much of the overall training volume is being consumed by DC type exercises versus those of more general nature in a structured training plan.

Though the idea of periodisation has been studied extensively, this final point of caution has only been addressed on a limited basis and no clear recommendation can be made yet at this point.

What about going sideways?

Another difficulty with dynamic correspondence is its relationship with change of direction performance (COD or agility). In terms of the training studies, traditional strength and power training methods (i.e. Olympic-style weightlifting and plyometrics) have been shown to enhance functional performance8 9.

Another difficulty with dynamic correspondence is its relationship with change of direction performance (COD or agility). In terms of the training studies, traditional strength and power training methods (i.e. Olympic-style weightlifting and plyometrics) have been shown to enhance functional performance8 9.

These training methods have been utilised in several training studies and are commonly used by strength and conditioning coaches. However, these traditional training methods have failed to improve COD performance.

This failure can be due to the commonality in the design of these studies, which include bilateral movements in the vertical direction. Conversely, COD movements often occur unilaterally in the vertical-horizontal and/or lateral direction, and require anteriorposterior (braking and propulsive) and mediolateral force production10.

Unfortunately, there is a distinct lack of research which investigates the correlations between unilateral horizontal jumping and COD performance. It could be speculated that since CODs require vertical-horizontal force production, horizontal jumping would be highly correlated with COD performance and could enhance COD performance with training.

Furthermore, for those sports requiring lateral force production (squash and tennis), the effect of lateral-type jumps needs to be investigated 11. Dynamic correspondence fails to highlight how a general to specific continuum, involving both bilateral and unilateral strength training can still have a great effect on performance while maintaining the sports specific qualities needed to succeed in the athletic arena.

Jumping, sprinting and changing direction are all general motor skills which need a variety of training methods to consistently overload and progress the athlete.

Conclusion

- It should be noted that the principle of specificity will vary greatly according to the training status, physical preparation levels, maturation status, and overall level of sport mastery of the athlete2.

- Athletes that are at a lower level of sports mastery may benefit from nearly any training modality and in turn could see positive transfer of training to commonly executed sport tasks; most likely caused by the neural adaptations occurring2.

- Transfer will take place much easier in lower level athletes due to their high sensitivity levels to physical activity. Their room for adaptation is much larger than their more advanced counterparts.

- As an athlete progresses in sport and training mastery, training methods must take on a greater emphasis of sports specificity in order to result in the desired adaptation1.

- This does not just mean Olympic lifting, you can use different overload variations.

Brett Richmond

Suggestions for future research

Effects of DC on different classifications of sport, not just rugby union such as:

- Track and field: Discus throwing

- Invasion: Soccer

- Racquet: Tennis

A need to develop a testing procedure which measures DC effect on off balance sports such as the single leg hop and hold. It can also be used as a functional assessment looking at ankle, knee, hip rotation and technical stability on a grading score line.

- Coaches: Come to our 1 day Coaching Athletic Development Course to see how to put theory into practice.

References

- Gamble, P. (2006). Implications and applications of training specificity for coaches and athletes. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 28(3), 54-58.

- Siff, M., & Verkhoshansky, Y. (Eds.). (2009). Supertraining (6th ed.). Rome: Verkhoshansky.

- Zatsiorsky, V., & Kraemer, W. (Eds.). (2006). Science and Practice of Strength Training (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Bompa, T, O., & Haff, G, G. (Eds.). (2009). Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training (5th ed.). Leeds: Human Kinetics.

- Kurz, T. (2001). Science of Sports Training: How to Plan and Control Training for Peak Performance. Island Pond, VT: Stadion Publishing Co.

- Stone, M. H., O’Bryant, H. S., Mccoy, L., Coglianese, R. & Lehmkuhl, M. (2003). Power and maximum strength relationship during performance of dynamic and static weighted jump. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,17, 140-147.

- Hori, N., Newton, R., Nosaka, K., & Stone, M. (2005). Weightlifting exercises enhance athletic performance that requires high-load speed strength. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 27, 34-40.

- Tricoli, V. A., Lamas, L., Carnevale, R., et al. (2005). Short-term effects on lower-body functional power development: weightlifting vs vertical jump training programs. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 19(2), 433-437.

- Kotzamanidis, C., Chatzopoulos, D., & Michailidis, C., et al. (2005). The effect of a combined high-intensity strength and speed training program on the running and jumping ability of soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 19(2), 369-375.

- Brughelli, M., Cronin, J., Levin, G., & Chaouachi, A. (2008). Understanding Change of Direction Ability in Sport. Sports Medicine, 38(12), 1045-1063.

- Blazevich, A. J., & Jenkins, D. G. (2002). Effect of the movement speed of resistance training on sprint and strength performance in concurrently training elite junior sprinters. Journal of Sport Science, 20, 981-990.

Client Testimonials

Vern Gambetta: GAIN founder

Vern Gambetta: GAIN founder

James Marshall is the consummate professional, always learning and working to make himself better. His focus is always on the athletes he working to make them better by exploring and discovering the dimensions of movement. He is a longtime active member of the GAIN professional development network. This gives him access to other professionals around […]

More

Comments

[…] Dynamic correspondence is just specificity of transfer. […]

Thanks Brett. Unfortunately, I still see the theory being trotted out with little or no understanding of application.

Students are taught this by people who just read research papers and write them, not by people who coach and observe and measure real athletes.

The mistakes become entrenched and lead to dogma rather than questioning and progress.