Principles of Training: Overload variations

“If your only tool is a hammer, then everything becomes a nail”

If your only way of overloading an athlete to cause adaptation is adding weight, then you are limiting what they can achieve. The overload principle is often defined by external load only.

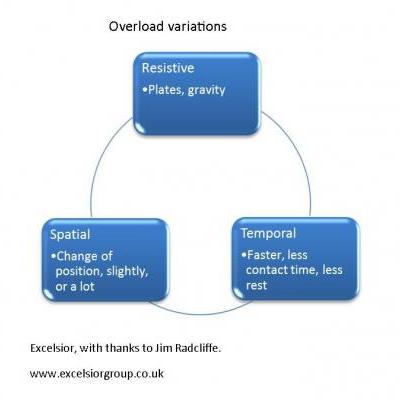

Not every sport, or every athlete needs to be loaded in the same way. One way of defining overload (as I learnt from Jim Radcliffe on GAIN 2011) is shown here:

Power= Force x distance/ time.

You can get more powerful by increasing force, or distance, or reducing the time to apply force or to cover distance.

The 3 overload variations being:

- Resistive: using gravity or external resistance.

- Temporal: do the same work but faster, with less rest, or less contact time.

- Spatial: train outside of the platform, small variations leading to big ones.

When planning training programmes, it is best to focus on one aspect at a time, whilst maintaining the others.

For example:

A fencer needs to be able to cover big distances, fast, with little or no external resistance, except gravity and air. It makes sense to work on spatial and temporal overload, rather than resistive.

Conversely, a tight head prop has to overcome massive external resistance in both the scrum and in the contact areas. It makes sense to concentrate on resistive overload, rather than spatial overload (although the latter is always amusing).

The relationship between the three

Whilst there needs to be a different emphasis at any one time, all 3 are inter related. It is diffcult to cover more distance (spatial) without the ability to produce force. That can be aided by resistive training. Similarly, having great strength, without the ability to move fast, or cover distance is useless in the sporting environment.

Whilst there needs to be a different emphasis at any one time, all 3 are inter related. It is diffcult to cover more distance (spatial) without the ability to produce force. That can be aided by resistive training. Similarly, having great strength, without the ability to move fast, or cover distance is useless in the sporting environment.

The problem occurs in training environments where one is the focus to the exclusion of all else. One current example is that British fencers are being told they have to be able to squat and deadlift twice their bodyweight! This shows a complete lack of imagination and understanding of what the sport requires.

Yes, most fencers could be stronger, and need to be, but that has to be applicable to what their sporting requirements are.

Conclusion

When setting out your plan, look at the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses, look at the sport requirements and adjust accordingly.

The 3 types of overload may help you start to systemise what you do and why.

“The best way to get better?…. is to get smarter!” Jim Radcliffe.

Hi James

We are studying principles of training in AS P.E. today and have used your piece on Overload. Great for the pupils to see the theory in action.

Becky Garner and the group have been reminiscing about your sessions – hindu squats and more.

JOhn

Hi John,

thanks for feedback. It is great to hear that the young athletes can connect the theory and practice.Hopefully they understand there is some method in all the madness.

[…] By this stage of the year, most athletes have built up a good foundation and are moving much better. With this in mind the focus of this term is improving strength and agility. Despite being fairly confident in my knowledge of strength training, James still managed to show me a new perspective […]